Cosa Buena: A good thing for art and public health in Oaxaca

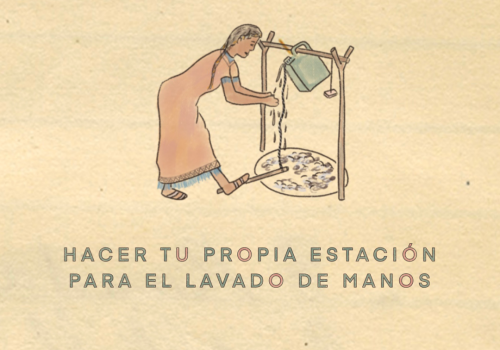

In Oaxaca, Mexico, Cosa Buena has taken its relationship with local artists to a new level in the coronavirus pandemic, collaborating with them to implement sustainable handwashing stations that serve as artistic sustenance as well as a public health measure.

Thu, May 14, 2020

In the city of Oaxaca, Mexico—known for its vibrant primary colors, iconic folk art and markets—one social enterprise has taken its relationship with local artists to a new level in the coronavirus pandemic, collaborating with them to create and design sustainable handwashing stations that serve as artistic sustenance as well as a public health measure.

Cosa Buena (which means “a good thing”) is a social enterprise in Oaxaca, Mexico that works with local artists to support the preservation of storied artistic traditions, and “to represent the depth of their cultural heritage and craft to outsiders.” Vera Claire founded Cosa Buena five years ago, with the aim of empowering Oaxacan artists and indigenous communities to navigate the international art and craft market without compromising the integrity of their beautiful work.

In normal times, they run critical literacy programs, gender equity workshops for female artisans, and art-focused cultural exchange programs and retreats. But when the coronavirus pandemic hit, travel ground to a halt, and the global economy took a hit. Soon the economic ripple effect also reached artists and artisans in Oaxaca.

Like many of us, Claire wondered if there was a way that she and Cosa Buena could help. “Personally, I was feeling a bit helpless but wanting to do something to support our community here through this crisis,” she said. “Preserving ancient crafts is a part of Oaxaca’s identity,” said Claire. “It’s not just what these communities do to make a living. It’s who they are.”

Mexico lacks equitable access to clean running water. “And so, you know, what does that mean in a pandemic when we’re being told washing your hands is one of the most important ways to protect yourself and others?,” asked Claire.

The idea to create handwashing stations to install at markets grew out of the reality of daily life in Oaxaca, where, Claire said, it was apparent from the beginning that many people do not have the privilege to be able to stay home and still be able to feed their families. “I began thinking, well what can we do to help support them, and handwashing was the number one recommendation. We immediately thought about local markets. Here in Oaxaca, local markets are a way of life, and people visit them very frequently, especially those who are living day to day. We zeroed in on markets as an area where risk could be high for transmission.”

Claire researched models of handwashing stations that had been implemented in densely-populated and low-resource settings, such as refugee camps. In consultation with recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), she and her husband developed a prototype that was approved by local authorities.

The model is operated by a foot lever, reducing the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission. The user only touches a bar of soap suspended by a rope.

In a matter of days, Cosa Buena pivoted from educational, art, and critical literacy progams to becoming a grassroots handwashing station factory. “We’re being given an opportunity now to really be creative and think of these solutions. We just hope that that inspires people — these are resources that are accessible and can be replicated across the world. It’s so needed now.”

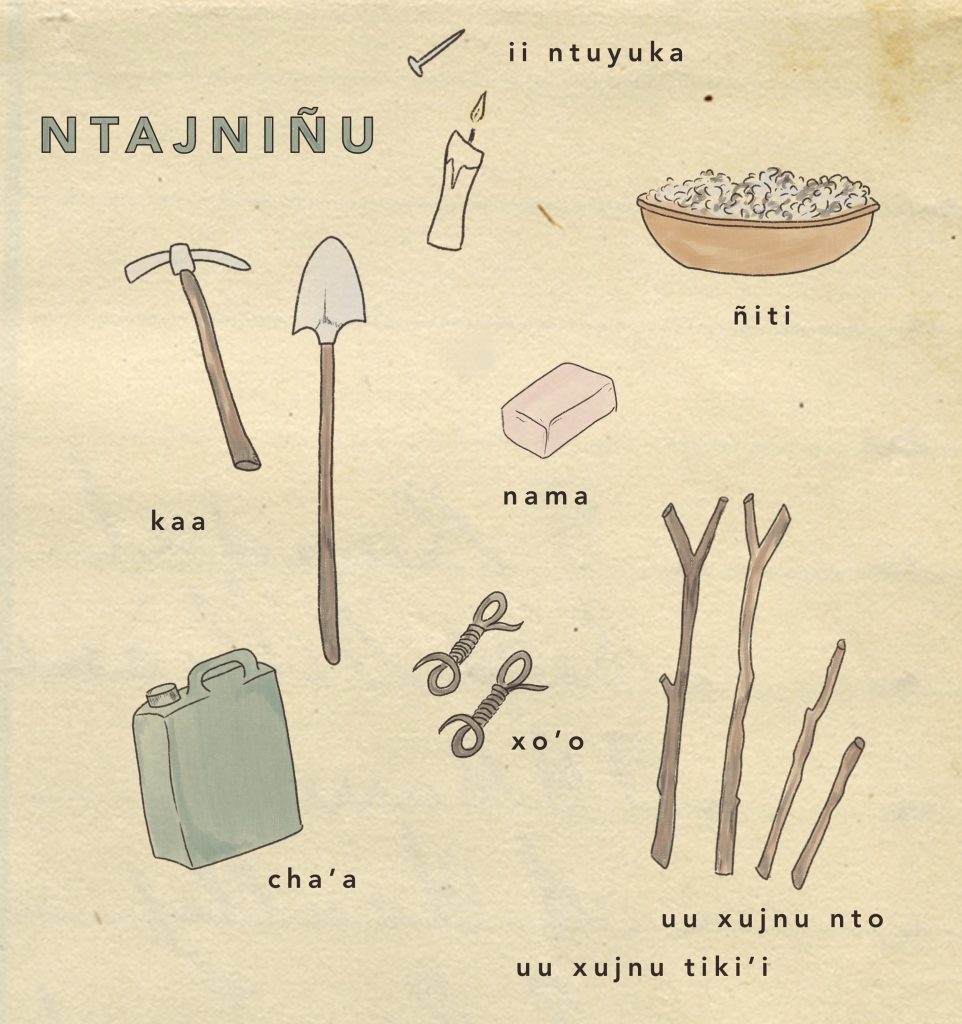

Here, illustrator Cathryn Rose presents the materials needed for communities to build their own handwashing station, shown here in the Mixteco language from Tijaltepec.

“In early April, there were some public health officials going around with pamphlets listing the symptoms of coronavirus and preventative measures — and even those kind of public health advisories were not always reaching many communities because they’re only offered in Spanish,” said Claire.

In response to the gaps in access to public health information, Cosa Buena developed instructional materials in Mixteco and Zapotec languages for remote and rural communities wishing to build their own handwashing stations. The stations can be built with locally-sourced materials, at little cost: wood or branches, string, soap, and a container for the water. One model can be built into the earth, using tree branches and sticks.

On April 7, they installed the first handwashing station at Oaxaca’s Mercado la Merced, a food market famous for its delicious antojitos, ‘small cravings.’ Later designs would involve local artistry, but this one was simple and functional.

“Because that was the very first one, we wrote instructions in Sharpie on the actual station,” said Claire. The writing, in Spanish, translates as, “step on the pedal, wash your hands.”

Since installation, between 2000 and 3000 people have used the handwashing station.

“Oaxaca is a really unique place with an incredible amount of talent in terms of the traditional craft and artistry that’s being preserved here in all of these indigenous communities, and we also have a lot of contemporary artists and street art – it’s a huge part of the identity of the community here,” said Claire. With a view to creating a space for social expression, she asked local artists to paint the stations. “The response was really wonderful, and there were a lot of artists writing, saying “I would love to do this.” It’s become a beautiful way to connect with our community.”

Each artist prepared a short text to accompany their handwashing station, which also serves as a message for community solidarity and support. Here, the artist Bouler has created a piece entitled “Renacer” (“Reborn”), inspired by the spirit mezcal, produced in Oaxaca through a process handed down through generations; a process that is a labor of love.

“Reborn from the ashes like the heart of the maguey plant (agave) in the making of mezcal,” the text reads. “Thus humanity will be reborn from within, leading from the heart.”

Artist Yesca created this handwashing station, entitled “Unidad y Esperanza” (“Unity and Hope”). “We are the disease, we are the cure, unity and hope is the vaccine,” the text reads.

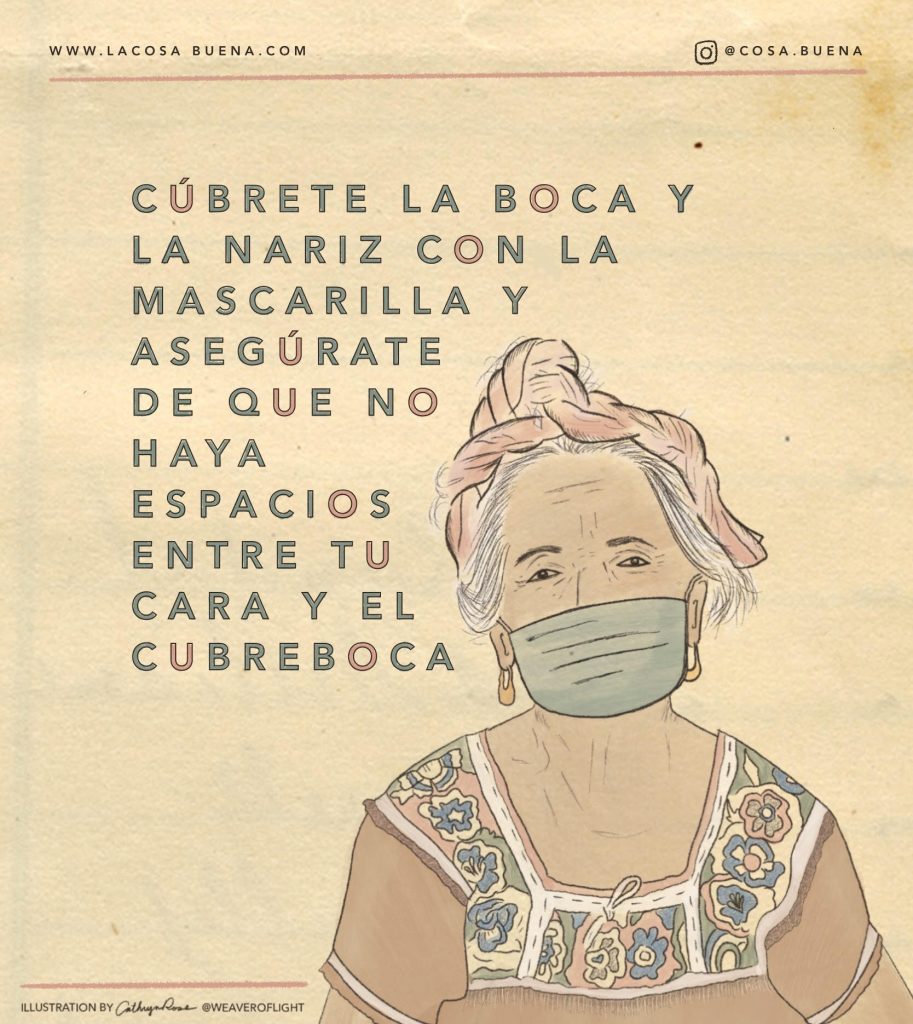

Alongside creating handwashing stations, Cosa Buena has also run a campaign informing people how to correctly wear, remove, and dispose of masks. “We’ve been really conscientious about representation and making the drawings look like people in the communities — using their languages, making the content feel familiar. I think that’s so important in public health messaging,” said Claire.

This drawing of a grandmother correctly wearing a mask was based on a photo of one of Cosa Buena’s community partners. “When I sent the drawing to her family, they were just thrilled about it,” she said.

Public health crises are not only crises for science and medicine, but crises of human connection. In the midst of them, we should not overlook the healing quality of art. Cosa Buena’s handwashing stations offer both form and function, meeting an important public health need while also providing artistic sustenance.

“We are all going through so many different emotions, internally trying to understand our place our role in this pandemic,” said Claire. “I think a lot of us understand that while all in the same storm, we’re not in the same boat. This pandemic has made disparities and inequalities within society very apparent. And I think art is a way to bring us together. Really, this was just an idea that popped in into my head and I’m so pleased with how it was received. People here have reached out and said, Oh, it’s so lovely to see them painted, and in our city that’s so full of color, it’s become another way for people to process and communicate what they’re feeling and what they hope for our community.”

To illustrate that last idea, here’s a handwashing station by artist Karel Muñuzuri. “Life is fragile, we hang from a pendulum with a thread of water,” the text reads. “The global situation that threatens us today presents a reality none of us could have imagined. Let us never forget that in difficult situations, development and community participation is the essence of our nature to solve problems and art, to sensitize the community and thus create sensible solutions. A community without art ends up destroying itself. “The ends and the means are not separable,” insisted Gandhi. “The means are the ends.”

This is a project from the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center and the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Share your #ResilienceStories and videos with us at resilience@atlanticcouncil.org and join us in sharing on social media: @atlanticcouncil, @ArshtRock, @DFRLab.