The climate insurance crisis

If your city can’t be insured, it can’t be financed

By Vito Dellerba Fri, Oct 24, 2025

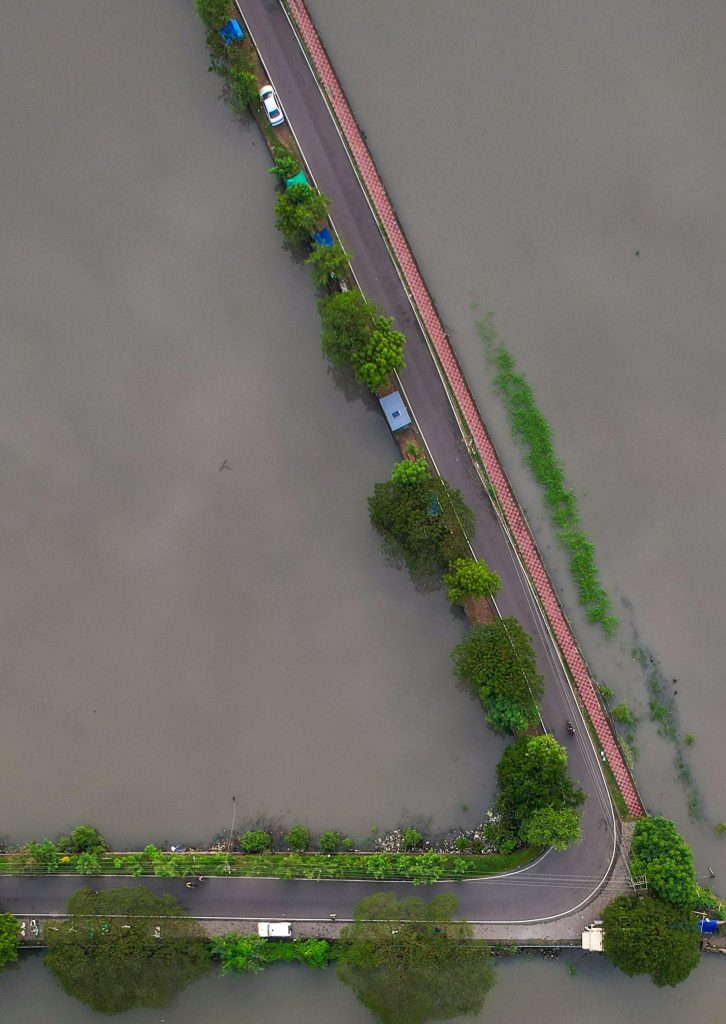

Let’s be candid. We’re entering a new climate era. Climate disasters and stresses are intensifying, and the insurance markets are beginning to price in the risk. For some cities, that’s not merely a threat, but rather a question of survival. If cities become too expensive to insure—or worse, become uninsurable—capital will disengage.

COP29 in Baku recentered the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). The goal is enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement as a commitment for developed countries to raise finance to support developing countries’ climate actions. COP29 raised the target to $300 billion in commitments annually; however, this comes with a larger goal of $1.3 trillion annually by 2035. But without a clear view of how these goals relate to insurability at the city-level, these investments are unlikely to have commercial support.

This article is part of our path to COP30 campaign. Our team and expert partners are sharing articles and research to deepen your understanding of the significance of this year’s UN climate conference. You can explore evidence-based analysis and policy insights that can drive change before the world gathers in Belém, Brazil.

Insurance as a market signal

Insurance is a proxy for risk perception. Essentially, insurers signal what risks are considered worthwhile. When insurers withdraw from providing coverage to specific markets, it signals that the underlying risk-return balance is no longer attractive.

Markets, consequently, respond. Insurers have begun to create geographic winners and losers along this insurance axis. For example, in Australia, insurers have begun withdrawing coverage from cyclone-prone regions in Queensland, citing unsustainable risk exposure. Similarly, in California, repeated wildfire events have led major insurers to pull back coverage, leaving homeowners with limited options and rising premiums.

Prices are changing; coverage is becoming less comprehensive; and the natural consequence is that the uninsured most vulnerable members of society or the public sector ends up paying the bill. This has knock-on effects. Namely, lenders realign collateral values. Investors begin to require increased returns. As a result, governments are forced to carry growing fiscal exposure as insurers of last resort.

The protection gap is not theoretical. It is a price signal that capital is already responding to. The protection gap refers to the difference between economic losses from disasters and the amount covered by insurance. It matters because it signals where capital is exposed without risk transfer mechanisms, increasing fiscal vulnerability. The European Central Bank cautions that the protection gap is growing and the Bank for International Settlements warns that certain geographies are heading towards an “insurability tipping point.” If we do not heed these warnings, we are merely designing finance for paper cities.

The affordability crisis

The affordability crisis isn’t about premiums: it’s about access. Banks do not finance real estate without insurance. When the cost of insurance increases because climate risk has increased, affordable housing becomes less accessible as a result. That affects housing markets, municipal budgets, and social cohesion.

The new flood insurance pricing methodology recently unveiled within FEMA’s Risk Rating Model 2.0 is a wake-up call: asset-specific risk-based pricing has arrived. The model shifts from traditional region-based flood zones to individualized property assessments. While the model was designed to improve equity by assessing individual property risks rather than broad zones, it revealed significant underpricing in high-risk areas. This led to premium increases, raising concerns about affordability and equitable access to insurance.

This new risk model has sent premiums upwards. It has doubled or tripled rates. Some regions have even seen a 342 percent spike in premiums. Thus, insurability and affordability are no longer distinct for many. This trend is bound to continue if proper urban resilience planning is not fast tracked. Cities must respond with the relevant resilience risk-based planning.

Three policy recommendations for COP30

For capital to flow into adaptation investments, cities must provide investors with a clear rationale for their return on investment (ROI). Cities need to prioritize a resilience portfolio approach that minimizes the insurance protection gap. Minimizing the insurance protection gap means reducing the share of climate-related losses that remain uninsured, which currently exposes cities, businesses, and households to significant financial shocks. A smaller protection gap signals to investors and insurers that the city is actively managing systemic risk, making it a more resilient and attractive investment environment. This requires integrating financial risk transfer mechanisms with physical adaptation measures so that both the probability and severity of losses are addressed.

Minimizing the protection gap

Risk assessment and transparent data

Cities must quantify climate risks using robust models and share this data with insurers and investors. Transparent risk mapping enables accurate pricing of insurance products and helps structure innovative instruments like parametric insurance.

Public-private sector risk transfer

Collaboration between municipalities, insurers, and capital markets is essential to design blended finance solutions that make insurance affordable and scalable. This could include catastrophe bonds, pooled risk facilities, or subsidies for vulnerable communities.

Incentivizing risk reduction

Insurance should reward adaptation measures—such as green infrastructure or flood defenses—through premium discounts or coverage enhancements. Linking physical resilience to financial incentives creates a feedback loop that accelerates adaptation.

As nations prepare for COP30, there are three clear priorities that need to be part of the climate finance agenda in Belém. First, cities need a framework to have ROI-aligned resilience portfolios. There cannot be subsidies for projects that have not considered this approach. The conversation on adaptation investments must be depoliticized and properly measure avoided losses, saved insurance coverage, and stabilized tax collections.

Second, national governments should make insurability a condition for concessional capital eligibility at the city level. Part of the NCQG should be made dependent on city-level portfolios that quantify risk reduction and insurance impacts. Yes, concessional public sector capital disbursements should prioritize cities that demonstrate measurable risk reduction and insurance impact through robust resilience planning.

Finally, the private sector has a clear role. There must be work on pricing and more weight to protection-gap quantification and mitigation in municipal credit rating models. This approach can incentivize positive protection-gap outcomes. For example, better credit ratings could translate to lower cost of capital, which would align incentives within city silos.

Belém must be the COP where we finally stop putting money into future write-offs and start putting money into resilience that investors will see value in. This is not utopia. Adaptation’s success is found in the plumbing: governance, data, delivery, and—yes—insurability.

This means that inscribing insurability into the UAE–Belém indicator activity is essential. Tying it to the NCQG eligibility further ensures that it can become a keystone metric for blended finance. If we get it right, we can turn adaptation from a cost center to a capital magnet.

Meet the author

Vito Dellerba is a Senior Fellow for the Atlantic Council’s Climate Resilience Center. In his current role as Senior Director of Infrastructure Financing for La Caisse, Dellerba focuses on the execution of high-impact sustainable infrastructure investments. He brings two decades of experience in the private financial sector and supports the center’s efforts to mobilize and innovate climate finance solutions.