This report is supported by the Instituto Clima e Sociedade (iCS) and is the result of a collaborative effort between National Confederation of Insurance in Brazil (CNseg), Marsh (Latin America), the Atlantic Council’s Climate Resilience Center, and iCS. Versão em português disponível aqui.

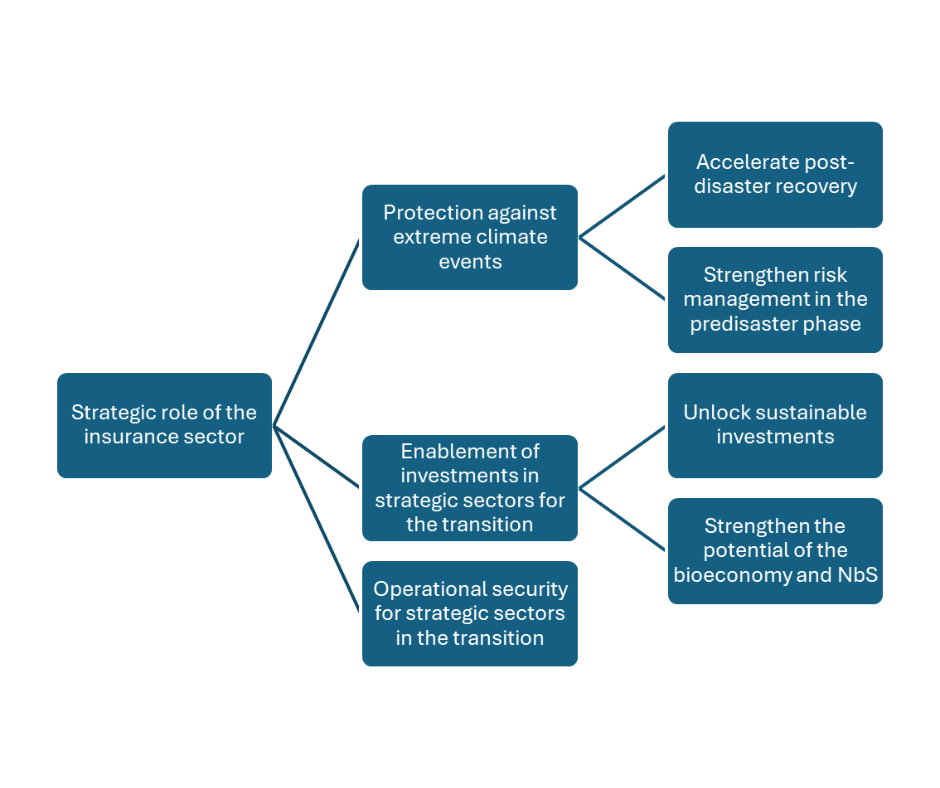

Insurance, as an instrument, can catalyze investment or reforms within an ecosystem, thereby reducing risk and protecting the most vulnerable. The loss of natural capital (i.e., resources) in our world will disrupt our societies, economically and politically. To avoid the cost of inaction and advance the role of the insurance sector, this paper aims to build awareness and capacity by equipping the Brazilian insurance sector with the knowledge and tools to invest in the creation of solutions and innovative approaches that reduce climate risks and enhance adaptation actions. The Brazilian insurance sector can play a key role in supporting and stimulating this agenda.

The trillions of dollars paid in insurance claims each year represent a significant contribution to building resilience of individuals, businesses, and community stakeholders—second only to government spending. It is critical to expand industry’s role in protecting society from the growing impacts of extreme climate events by offering mechanisms that consider solutions for long-term resilience to support the rapid recovery of affected areas, assets, and communities, especially the most vulnerable.

Although several lines of insurance offer coverage for these climate risks, insurance access remains low. Further, the protection gap against climate disasters—that is, the difference between total economic losses and the insured amount—remains significant. For recent disasters, the gap has reached a shocking 91 percent. Thus, many individuals and businesses lack protection from insurance policies, leaving themselves exposed to financial and physical risks.

Effective insurance policies, however, can bridge this gap. They can enable investment and operational security for structural reforms in key transition sectors such as infrastructure, energy, industry, and agriculture. By providing stability and predictability, the insurance sector can act as a powerful catalyst to scale up the bioeconomy.

There are also significant opportunities for both low-carbon agriculture and livestock production. Sustainable practices such as integrated crop-livestock-forestry (ILPF) systems, no-till farming, regenerative agriculture, and agroforestry systems (SAFs) position the agricultural sector to directly contribute to conservation, greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions, and increased climate resilience. Further, these practices can also reduce climate-specific agricultural risks such as prolonged droughts, soil erosion, and pests. Agricultural insurance has the potential to become a strategic instrument in the transition to a low-carbon economy and in valuing environmental assets. This kind of insurance can incentivize sustainable and resilient practices and the adoption of energy-efficient mechanisms.

More than compensating losses from adverse climate events, insurance can proactively encourage sustainable practices through pricing, underwriting, risk-management practices, such as crop diversification and managing financial flows, and stakeholder engagement between farmers, the financial sector, and governments. Quantifying risks for natural resources is difficult, but with innovative mechanisms and better modeling, the challenge of risk management can be surmounted.

The private sector cannot afford inaction. Beyond environmental gains, the practices examined in Brazil’s insurance industry show how bioeconomy activities can enhance the efficient use of natural resources, improve production stability, and open new economic opportunities. This convergence between environmental conservation and innovation highlights the need to expand nature-based solutions (NbS) in Brazil. For the insurance industry, incentivizing sustainable production practices is strategic. Not only can these new business opportunities lead to innovative products and services, but NbS can also mitigate systemic risks that directly impact insurers’ operations by generating benefits related to carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and climate adaptation and resilience.

Key findings

This report examines the role of Brazil’s insurance market in addressing climate and biodiversity-related risks. By providing a diagnostic overview of the current Brazilian insurance landscape, the report aims to support the future development of insurance products dedicated to climate adaptation, environmental conservation, nature-based solutions (NbS), and bioeconomy.

The analysis is based on desk research and interviews with insurance companies, industry associations, and other stakeholders across the value chain.

As the current protection gap is large and puts individuals, businesses, and communities at risk, we list key findings that emerged based on research and interviews. These insights address the insurance landscape in Brazil yet remain relevant for similar markets globally.

Insights on biodiversity

Although Brazil’s insurance sector has begun to incorporate climate risks into its analyses and product development, there is still limited attention to the integration of nature-related risks like biodiversity loss. There is a growing awareness that climate change and biodiversity loss are deeply interconnected. Further, many now recognize that nature-based solutions can mitigate carbon emissions while increasing biodiversity.

Brazil’s forest restoration and conservation operations are often exposed to wildfires, extreme droughts, storms, and invasions for illicit exploitation. Insurance coverage for forests—that is, coverage that protects native vegetation and supports conservation and restoration projects—bears a high value for communities and businesses that rely on the resources. Insurance could help derisk projects for investors. However, these risks are characterized by low predictability, high severity, and seasonal occurrences, making traditional pricing difficult and reinsurance availability limited.

There are limited climate and nature-related insurance products and a scarcity of market studies, models, and reliable data on disasters and their respective impacts on ecosystems. Limited data also exists on the impact of innovative and sustainable agricultural practices. This lack of technical parameters and methodologies to measure the positive impact of such practices on risk reduction complicate efforts to develop nature-related insurance products at scale. There is a need to foster a risk and insurance culture, especially in the bioeconomy sector, and to build capacity at the executive, commercial, and technical levels to recognize the impact and adopt methods for better insurability.

Insights on data gaps

Without sufficient data, risks are considered high by default. Not only is there a need for data, but there is a need for the effective use of data to manage the risks and allow for the implementation of risk-reduction methods. For the insurance sector, unreliable or limited data on frequency of climate hazards and severity of losses makes it difficult to accurately model or price risks, which results in treating them as high-risk factors. If risks can be more accurately gauged, consumers and the industry can develop better risk-reduction strategies and plan for more affordable coverage plans.

Insights on the risk-management and insurance landscape

Current Brazilian agricultural risk-management instruments include public policies such as the Rural Insurance Premium Subsidy Program (PSR); the Agricultural Activity Guarantee Program (PROAGRO), which protects producers from losses resulting from natural phenomena and covers financial obligations related to rural financing; the Guarantee for Harvest (Garantia-Safra), a support program for family farming affected by droughts or excessive rainfall; and the Minimum Price Guarantee Policy (PGPM), aimed at correcting price distortions.

Notably, other initiatives focus on insurance coverage and risk reduction. The development of the Brazilian Sustainable Taxonomy (TSB), for example, aims to establish clear and verifiable criteria for directing investment flows to high impact and innovative activities. The Ecological Transformation Plan, by the Ministry of Finance, lays the groundwork for public policy development and government programs aimed at driving Brazil’s transition toward a sustainable economy. Further, Plano Safra is a major public credit program that supports farmers and has increasingly incorporated sustainability criteria, technical assistance, and favorable financing conditions for high-productivity, low-impact agricultural practices. Other initiatives such as Pronaf and the ABC+ Plan (2020–2030) promote family farming and low-emission agricultural practices.

Insights on the National Bioeconomy Strategy

The bioeconomy agenda has the potential to position Brazil as a global leader in the transition to a low-carbon, resilient economy committed to environmental conservation. With value chains based on bioproducts, bio-inputs, and traditional knowledge, Brazil has a tangible opportunity for income generation that still adds value to natural resources in a sustainable manner.

In 2024, the government launched the National Bioeconomy Strategy, which sets out guidelines for designing and implementing public policies to strengthen Brazil’s bioeconomy, highlighting essential areas for sustainable development, such as productive forest management that does not compromise natural resources, with a focus on SAFs and ILPF. The Brazil Platform for Climate Investments and Ecological Transformation—launched the same year—aims to attract international investments in green energy, sustainable agriculture, and NbS. Financial tools such as blended finance, green bonds, and nature bonds provide avenues for insurers to invest in climate resilience while managing risks tied to both the physical and transition impacts of climate change.

For the insurance sector, besides the TSB, CNSP Resolution No. 473/2024 establishes criteria for the classification of insurance and open private pension plans as sustainable. Such regulatory changes are paving the way for the development of nature-related insurance products.

Insights on the coverage gap

There has been concerning shrinkage in the insured portion of Brazil, which decreased by 50 percent between 2023 and 2024. This reduced the total insured area by seven million hectares, raising concern among producers and the insurance sector. This decline is directly linked to annual budget cuts in the PSR, which provides a subsidy that reduces the cost of insurance for producers. Additionally, according to data from the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, insurance covers less than 8 percent of cultivated land in Brazil, revealing significant exposure to climate risks.

Introduction

Brazil holds a unique position on the global stage. Its vast preserved ecosystems and invaluable biodiversity play a vital role in climate regulation, the mitigation of extreme weather events, and the provision of essential ecosystem services that support life and economic activity. However, no one has standardized their full economic value.

This report explores how the insurance industry assesses the value of nature and how it can better account for it in the future. In this context, there are clear opportunities in the bioeconomy. Forest protection and degraded-area recovery initiatives aligned with the advancement of low-carbon agriculture and livestock production can complement these priorities. The maintenance of large, forested areas through preservation or restoration projects is a key action for climate mitigation and adaptation. By scaling up sustainable practices—such as integrated crop-livestock-forestry (ILPF) systems, no-till farming, and agroforestry systems (SAFs)—the agricultural sector can contribute directly to ecosystem conservation, greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions, and increased climate resilience.

Notably, there is strategic opportunity in the insurance sector. By putting a price on risk, insurers send a powerful signal about the severity and frequency of climatic events. This, in turn, can incentivize risk-reducing behavior. The insurance sector must operate in an enabling environment and needs to accelerate its action in adaptation and mitigation. The trillions of dollars paid in insurance claims each year represent the second-largest monetary contribution to individual, business, and community resilience after government. Insurance is, therefore, not only a risk management tool, but also a critical instrument for financing and implementing a more resilient and sustainable development model.

Insurance for climate, nature, and the bioeconomy

Given the country’s deep and rich biodiversity, there is a clear need to align with emerging global recommendations. In June 2021, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)—”a market-led and science-based initiative supported by national governments, businesses, and financial institutions worldwide”—was established to help businesses and financial institutions manage nature-related risks and opportunities. Modeled after the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), TNFD applies the same priorities to set clear processes and expectations from risk assessment to disclosure. Thus, a similar structure for nature and biodiversity-related risks is emerging and underscores how environmental factors, whether climatic or ecological, directly affect financial stability, business models, and long-term asset value.

Although climate and nature risks are distinct in definition, they are deeply interconnected in practice. Their impacts often overlap, compounding social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities.

The conversion and degradation of natural ecosystems not only increase GHG emissions—exacerbating the climate crisis—but also undermine the ability of these ecosystems to regulate climate and buffer against future extreme events. For example, biomes such as the Amazon, the Cerrado, and the Atlantic Forest play a critical role in rainfall patterns and climate stability across vast regions of Brazil. This stability is essential for highly vulnerable sectors such as agriculture, livestock, and hydroelectric power generation. Preserving these ecosystems is therefore strategic for economic resilience and the sustainability of climate-dependent activities.

The role for insurance

The insurance sector can absorb part of the risks associated with ongoing economic, social, and environmental transformations. This includes physical risks linked to extreme weather events and the transition risks related to key sectors of decarbonization. Beyond risk absorption, insurance can act as a catalyst for change. Through pricing, underwriting, and risk-management practices, insurers can influence the behavior of policyholders and society at large. They can encourage more resilient and sustainable practices, helping internalize environmental externalities and reducing systemic risks.

Brazil’s insurance sector has begun to incorporate climate risks into its analyses and product development. Yet nature-related risks earn limited attention. The intersection between insurance, nature, and the bioeconomy is, however, already gaining traction in academic circles and public policy discussions. Experts have increasingly explored how the insurance sector can support NbS, encourage sustainable practices such as regenerative agriculture, and help individuals, businesses, and communities manage and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Brazil’s vast natural wealth positions the country as a strategic setting to integrate environmental sustainability into the insurance sector. Insurance products designed to address nature-related risks remain limited, but the sector increasingly understands that nature-based solutions do more than mitigate emissions. These solutions can increase biodiversity, protect water sources, safeguard communities from extreme weather events, and even improve community health.

The focus now is on the development of more integrated insurance solutions. The link between environmental sustainability and risk management will become increasingly central in the coming years. Both public policy design and the creation of innovative insurance products and services will evolve in response to the transition to a low-carbon, resilient, and sustainable economy.

Understanding the bioeconomy agenda

In the literature, three main perspectives shape the bioeconomy agenda:

- The biotechnological perspective: This perspective considers commercial applications across various sectors. Regulatory frameworks related to science, technology, and innovation can enable this approach, ensuring the integration of biotechnology into traditional industries.

- The bioresources perspective: This perspective aims to replace fossil-based raw materials with sustainable biomass. As such, it involves the production of biofuels, biorefineries, and renewable energy. Regulatory instruments targeting biofuels, sustainable land use, and biomass processing are central to this vision.

- The bioecological perspective: This perspective centers on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. It calls for the inclusion of traditional knowledge and promotes organic, low-carbon agricultural practices. Key regulations focus on protecting forests, native vegetation, and sociobiodiversity, ensuring the responsible and sustainable management of bioecological assets.

Case study: Brazil’s Plano de Transformação Ecológica (PTE)

The PTE, created by the Ministry of Finance, lays the groundwork for public policy development and government programs aimed at driving Brazil’s transition toward a sustainable economy through six thematic pillars.

The second pillar focuses on technological densification, which is relevant to the themes of bioeconomy and agrifood systems. PTE calls for technological development aligned with the Plano Safra, a major public credit program that provides subsidized financing for farmers of all sizes. The program has increasingly incorporated sustainability criteria, technical assistance, and favorable financing conditions for high-productivity, low-impact agricultural practices. These efforts align with other initiatives that promote family farming and low-emission agricultural practices, such as the Pronaf and the ABC+ Plan (2020–2030).

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change has established the National Secretariat for Bioeconomy and the government launched the National Bioeconomy Strategy. The latter highlights essential actions like productive forest management with a focus on SAFs and ILPF. It also introduced a multisector governance framework that outlined key objectives such as the creation of targeted financial instruments and the redirection of public and private funding flows to support sustainable value chains and expand market access for products derived from sociobiodiversity and forest-based agriculture.

The sixth pillar focuses on new green infrastructure and adaptation. It prioritizes climate security, prevention, and adaptation to crises and climate change. It directly references the New Growth Acceleration Program (Novo PAC), which is a notable investment for resilient infrastructure projects. In 2023, Brazil founded Novo PAC to invest BRL 1.7 trillion ($320 billion) across all Brazilian states. This investment policy plan seeks to reduce the impacts of climate change, mitigate the risks of natural disasters, and progressively incorporate stronger environmental and social criteria across all its investments.

As part of the consolidation of this pillar, the federal government is currently developing the New National Climate Plan (Plano Clima), which will serve as the primary planning and coordination instrument for Brazil’s climate change response. In parallel, national strategies for climate mitigation and adaptation will be refined based on sectoral and territorial assessments. Another important national-level initiative was the launch of the Brazil Platform for Climate Investments and Ecological Transformation. It aims to attract international investments in green energy, sustainable agriculture, and NbS. These opportunities allow insurers to diversify their portfolios and contribute to Brazil’s green transition. Through financial tools such as blended finance, green bonds, and nature bonds, insurers can invest in resilience while managing risks tied to both the physical and transition impacts of climate change.

According to a study by the Climate Policy Initiative, there are different interpretations of what the bioeconomy is. However, they all share a common foundation: biological resources and their innovative use can drive development. The primary distinction lies in how innovation is understood and applied.

In industrialized countries and multilateral organizations—typically with lower biodiversity—the bioeconomy centers on biotechnology and bioresources. There is a special emphasis on food security and climate change mitigation. In contrast, countries rich in biodiversity tend to view nature conservation as a cornerstone of their socioeconomic development, even though their strategies and conceptual frameworks may vary.

There is no single model of bioeconomy that fits Brazil. Given the country’s continental scale and its diverse social, economic, and ecological realities, it is essential to adopt a combination of approaches. This plural strategy allows for more efficient and inclusive valorization of different regions across the country. Based on a literature review and interviews with the Brazilian insurance sector, the following sections provide an overview on the areas that need to be prioritized for implementing innovative financial solutions. Namely, these include: establishing legal frameworks and public policies; engaging with the insurance sector; closing the protection gap; collecting robust data for sustainable solutions; and advancing agricultural risk-management policies.

The Brazilian government has played a central role in establishing legal frameworks and public policies to support the bioeconomy, sustainable agriculture, and the achievement of national climate targets. These initiatives provide legal certainty. They also offer clear guidelines to the market and create an enabling environment that attracts investment and mobilizes the necessary implementing financial instruments. Namely, these efforts are captured in the Ecological Transformation Plan—or Plano de Transformação Ecológica (PTE)—and the country’s international commitments.

Case study: International commitments

Brazil has advanced several climate commitments since it formally ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016. On the international stage, during the 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference (CO29) in Baku, Brazil reaffirmed its climate commitments under the agreement, pledging to:

- Reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by 59 percent to 67 percent by 2035, compared to 2005 levels.

- Reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

- End illegal deforestation by 2030.

- Restore twelve million hectares of forest by 2030.

This new Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is strategic not only for reducing emissions but also for valuing Brazil’s natural capital, protecting biodiversity, generating green jobs, and advancing the transition toward a regenerative and low-carbon economy.

As host of the Group of Twenty (G20), Brazil also set an agenda that prioritized the global bioeconomy. This G20 Bioeconomy Initiative leverages renewable biological resources for sustainable economic growth through ten nonbinding principles. The initiative also underscores the importance of fair compensation for Indigenous traditional knowledge and encourages local bioeconomies. By integrating local economies into global value chains, the initiative ensures that biologically rich nations can actively participate in global economic growth.

Brazil championed South-South cooperation and highlighted the essential role of biodiversity in sustainable economic development. The country’s leadership reinforced the importance of placing biodiversity at the center of global discussions on economic progress.

The importance of insurance-sector engagement

The mobilization of insurers is a key element of this process. Effective and inclusive discussions among professionals in the Brazilian insurance sector can consolidate necessary information and clarify the gaps and opportunities. These insurers have clear insight into the challenges to implement or scale relevant insurance products and mechanisms.

While recent regulatory changes are paving the way for the development of nature-related insurance products, insurers must advance innovative climate strategies. For example, the Brazilian Sustainable Taxonomy and the National Council of Private Insurance Resolution No. 473/2024, provides for the classification of insurance and open private pension plans as sustainable. While this critical regulatory change laid the groundwork, insurers need to develop products that are financially viable, socially responsible, and supportive of environmental sustainability.

By connecting insurers, reinsurers, investors, policyholders, universities and research institutes, associations, and regulators (among others), policymakers can better address gaps related to the adaptation of existing products and the development of new ones. Current gaps include limitations in coverage for climate risks (insufficient to cover large-scale catastrophic events); scarcity of market studies, models, and reliable data sources on disasters and their impacts on ecosystems; unaddressed opportunity to foster a culture of insurance among the population and within the bioeconomy sector; and insufficient capacity at executive, commercial, and technical levels.

Finally, there is also significant potential in parametric products. These products pay out based on established triggers, offering greater agility in responding to extreme events. They are also used for emerging products like carbon or biodiversity credits insurance. However, there are still challenges despite the clear potential. The insurance-sector actors and public policies must better define insured parties, beneficiaries, and models for public-private financing, especially concerning climate resilience projects and ecosystem protection.

Closing the protection gap

Despite Brazil’s historically limited exposure to natural catastrophes, the growing frequency and severity of climate-induced disasters has increased its insurance sector’s awareness of climate-related risks. The physical risks that cause the greatest losses—both in the public and private sectors—are hydrological risks like extreme rainfall and flooding. These hazards damage infrastructure, property, and urban areas; and droughts. Consequently, they result in substantial agricultural losses and threaten electricity generation due to the country’s high dependence on hydropower.

These impacts also affect existing insurance products that cover climate-related risks, such as property insurance and agricultural insurance. Thus, insurance can serve beyond a post-disaster response. It can also play a proactive role in providing security for structural reforms. Many sectors are both exceptionally vulnerable to climate change and essential to a successful transition, such as agriculture or and infrastructure. Risk-transfer mechanisms must go beyond traditional approaches. The insurance sector can shift the financial burden of climate-induced damage from policyholders to insurers. Simultaneously, it can incentivize policyholders to adopt risk-reduction strategies.

Nevertheless, insurance penetration remains low. The protection gap—i.e., the difference between total economic losses and the insured amount—remains significant across the country. For example, twelve consecutive days of rain caused floods and landslides in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Only a small portion of these losses—BRL 6 billion—was covered by insurance. As a result, the protection gap for this event was calculated at 83 percent, revealing that a large share of affected individuals and businesses lacked the protection that insurance policies could have provided.

The cause behind the gap

What causes this notable gap? Informational, economic, and behavioral factors—ranging from diminished trust and awareness about insurance products to risk perception—exacerbate it. The lack of widespread coverage worsens the accessibility of insurance. Without a significant insured base, it is difficult for insurers to diversify risks. This leads to adverse selection and undermines one of the fundamental principles of insurance. Namely, expanding the pool of policyholders helps distribute risks more effectively and contributes to more accurate and affordable pricing.

This limited coverage for climate-related disasters also hinders risk modeling. Current data does not provide a sufficiently robust loss history to support reliable models. This lack of quality data complicates decisions around pricing and underwriting. As a result, insurance remains inaccessible for a large portion of the population, perpetuating a cycle of vulnerability.

The high protection gap highlights the need for greater innovation. For example, stakeholders have developed parametric solutions based on extreme weather events, but few have widely adopted them. Insurers in Brazil can consider how to expand their application to infrastructure and other relevant sectors.

Despite these gaps, the Brazilian insurance sector has already shown a significant commitment to climate risk transparency. For example, it became the first insurance market in the world to endorse the TCFD. The industry also released the Rio Declaration on Climate Risk Transparency in 2018. In an unprecedented move, the industry became the world’s first to commit to actions that align with the TCFD, emphasizing that unchecked climate change poses significant threats to the sustainability of insurance markets and the financial system. Additionally, Brazil was the first country in Latin America to require the consideration of sustainability risks—including climate risks—in risk management, underwriting, and product development processes.

Collecting robust data for sustainable solutions

Rural insurance can serve as a strategic instrument in the transition to a low-carbon economy and valuing environmental assets. Essentially, rural insurance is a specialized but broad coverage for agricultural workers and businesses. It protects against financial losses for various agricultural and rural practices, ranging from livestock deaths to property damage.

Insurance can do more than compensation alone. It can also encourage sustainable practices that contribute to climate resilience and GHG emissions reduction. Systems like the ILPF, agroforestry systems, regenerative agriculture, and forest restoration not only help mitigate emissions but also reduce exposure to climate risks such as prolonged droughts, soil erosion, and pests.

Understanding the challenges

One of the major challenges, however, lies in establishing robust technical parameters and methodologies to measure the positive impact of such practices on risk reduction. There is a need to concentrate on empirical evidence for sustainable production systems. These datasets should underscore the consensus that sustainable practices generate less variability in yield, have greater resilience to extreme events, and represent lower risk for insurers. This evidence would enable differentiated insurance premiums that recognize the technical and environmental merits of these producers and function as a direct economic incentive for their adoption.

Currently, rural insurance pricing largely relies on established historical datasets derived from conventional production systems, especially large-scale monocultures. They offer statistical predictability for actuarial calculations, which facilitate product design and premium settings.

Conversely, more innovative or sustainable agricultural practices lack robust and continuous data on their performance. Since these practices are relatively recent and often implemented at smaller scales, they lack sufficiently long and systematic time series. Further, they are often spread across regions with high socioenvironmental heterogeneity and frequently associated with more complex production arrangements. These factors make it challenging to accurately feed the statistical models used by insurers to assess sustainable interventions with the same clarity for more established practices. Without this technical support, it becomes difficult to accurately measure the risk profile of these systems. As a result, the premiums can be higher. There can be a distinct lack of coverage, even when qualitative and empirical data suggest the benefits of sustainable approaches.

Understanding the opportunities

From the perspective of rural insurance, one of the most challenging—and most promising—fronts is forest insurance. This type of insurance aims to protect native vegetation and support conservation, restoration, or the sustainable use of natural forests. Unlike commercial forests, whose assets are priced based on well-defined silvicultural standards like productivity per hectare or replacement costs, native forests lack a directly measurable market value.

Their value is linked to complex ecosystem functions like carbon sequestration or regulation of the hydrological cycle. These attributes do not follow homogeneous or linear measurement parameters. Instead, they vary according to biome, successional stage of vegetation, soil type, and rainfall patterns, among other factors. Economically valuing these assets—and consequently insuring them—requires interdisciplinary methodologies that are still under development, such as opportunity cost analyses, carbon stock and flow modeling, and territorially based environmental impact assessments.

Additionally, forest restoration and conservation operations are often exposed to catastrophic risks such as wildfires, extreme droughts, storms, and illegal invasions. These hazards threaten not only the environmental assets but also the economic viability of the project itself. These risks typically occur seasonally and display low predictability and high severity. As a result, traditional pricing is more difficult. Reinsurance opportunities are limited, especially in the international market, which still has limited familiarity with tropical biodiversity-based assets. The lack of reliable and segmented claims history for this type of asset exacerbates the problem. Without sufficient data, risks are considered high by default, which results in prohibitive premiums or even the impossibility of coverage. Another avenue for this type of insurance product is carbon and biodiversity credits.

Advancing agricultural risk-management policies

Agriculture is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events. Thus, Brazil’s agricultural risk-management instruments are increasingly critical. These instruments, including public policies such as the Rural Insurance Premium Subsidy Program (PSR), the Agricultural Activity Guarantee Program (PROAGRO), the Guarantee for Harvest (Garantia-Safra), and the Minimum Price Guarantee Policy (PGPM), aim to mitigate the risks imposed by climate change on agricultural production, especially in the face of excessive rainfall and recurring droughts.

In addition to public financing, private funding plays a significant role in these programs, primarily coming from premiums paid by producers for rural insurance and participation in PROAGRO. In 2018, an amount exceeding BRL 5 billion was paid through rural insurance premiums (considering the total paid by producers plus government subsidies through PROAGRO) and the programs Garantia-Safra and PGPM.

However, given the large coverage opportunity under the rural insurance program, this was still limited coverage. These policies and government programs, if coupled with support from the private insurance market, will strengthen risk management and financing solutions, allowing the insurance market to expand.

The vanishing insured

Since the 1960s, climate change reduced agricultural productivity by 21 percent. Increased productivity per hectare is crucial for global food security and sustainable development. It can reduce the pressure to expand agricultural areas, which mitigates climate-related losses. But it also enables producers to direct investments toward technological development and the adoption of more sustainable agricultural practices, preserving soil health and promoting continuous productivity gains.

The insured portion of Brazil shrank by 50 percent between 2023 and 2024. This reduced the total insured area from fourteen million to seven million hectares. With support from the federal government through the PSR, insurers have been able to increase their risk-taking capacity and improve products and services, aiming for the ambitious target of protecting twenty million hectares.

However, government-backed rural insurance covers less than 8 percent of cultivated land in Brazil. In large part, this is because of a spike in the average premium price per hectare. In 2022, it rose to BRL 500, up from BRL 100 in 2019. This increase is associated with higher indemnities, which are driven by the greater frequency of climate disasters. As a result, insurers have adopted stricter risk analyses, avoid regional concentrations, and seek diversification in insured crops.

Amid this reality, the PSR becomes even more important. But its funds have faced successive budget cuts. The insured area was reduced in 2022 due to adjustments in policy prices driven by higher climate-risk exposure. In 2023, the approved PSR budget was reduced, with disbursed amounts falling below projections. This could trigger cost increases of 20 to 40 percent for producers. Nevertheless, it is important to note that, compared to other countries, Brazil has the lowest rural insurance premium-subsidy rate and fewer resources supporting agricultural production.

Conclusion

The complex issues related to climate, biodiversity, and bioeconomy exceed the isolated capacity of insurers. Overcoming these obstacles in a new climate era requires the coordinated mobilization of robust public policies, intersectoral integration, and the establishment of institutional and financial frameworks. With proper design, these actions can unlock strategic investments, mitigate systemic risks, and promote the realignment of national productive development.

In this context, insurance is a key sector. For example, earlier this year, Brazil issued its first-ever insurance-linked securities. With this in place, forest risks could be transferred to capital markets like other catastrophe bonds. Within an integrated system of economic and environmental transformation, insurers act not only as risk mitigators but also as drivers for sustainable practices and resilient development. Breaking the cycle of underprotection requires close collaboration among the Brazilian government, the financial sector, and businesses. Together, they can create effective incentive mechanisms, develop solid technical foundations, and build risk-sharing instruments that enable large-scale support for sustainable production systems. Insurance can and should be a central part of this transformative solution.

But to achieve this, policies and solutions must go beyond traditional practices, conventional pricing methodologies, and current coverage options. They must rather pave the way for innovative products aligned with socioenvironmental challenges.

COP30 represents a unique strategic opportunity for the insurance sector in Brazil and globally. The sector must establish insurance as both a financial protection tool against the impacts of extreme climate events and as a fundamental enabler of investments in resilient infrastructure, nature-based solutions, and the transition to a low-carbon economy. By taking a proactive stance, insurers can influence regulatory policies and innovative financial mechanisms. At COP30 and beyond, they can expand access to insurance protection and foster sustainable production practices.