Overview

Hot days in Buenos Aires are already dangerous, particularly in disadvantaged areas where temperatures can be as much as 15°C hotter than rural surroundings, and current extreme conditions are set to become twice as common.

Some dense, paved areas are already as much as 15°C hotter than the surrounding countryside. These hotspots are likely to become more prevalent by 2050.

In baseline climate conditions, Buenos Aires loses over USD 115 million (ARS 10,926 million) in a typical year from reduced worker productivity on hot days—and this could triple over the next three decades. Losses from heat in Buenos Aires are steepest in manufacturing, trade, and transport services, including around its rapidly growing port.

The impacts of heat are expected to be greatest among the two million residents who live in informal settlements such as settlement Villa 31, where temperatures are often the highest and access to cooling options is most scarce.

Buenos Aires can scale up existing programs of heat mitigation, with a strong focus on protecting its most vulnerable residents.

Impact of extreme heat

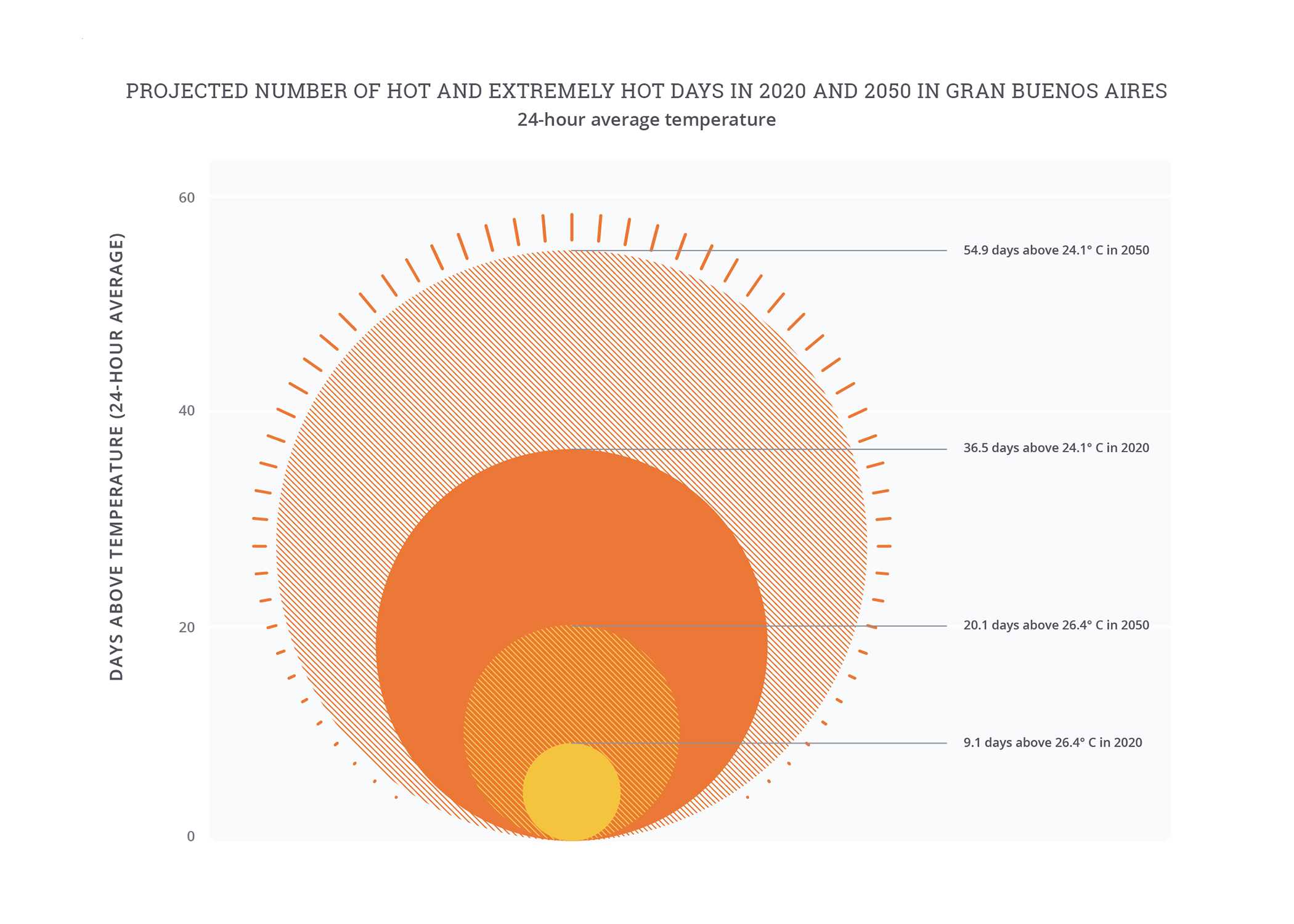

Hot days in Buenos Aires1 are already dangerous, particularly in disadvantaged areas where heat is concentrated, and current extreme conditions are set to become twice as common.2 The climate of Buenos Aires is generally moderate, though the top ten hottest days in a typical year already have twenty-four hour average temperatures of 26°C, and highs of up to 43°C have been recorded in the city.3 Without action to curb emissions, by 2050 these extremes will become more common with twenty days as hot or hotter than the current local extreme. Heat is concentrated in more built-up areas where many of the city’s less affluent residents live and work, with temperatures as much as 15°C higher than rural surroundings.4 For example, Retiro, which is home to transportation hubs such as the major long-distance bus terminal and train lines traveling north, is warm due to the prevalence of exposed, paved areas and the density of Villa 31, a nearby informal settlement.

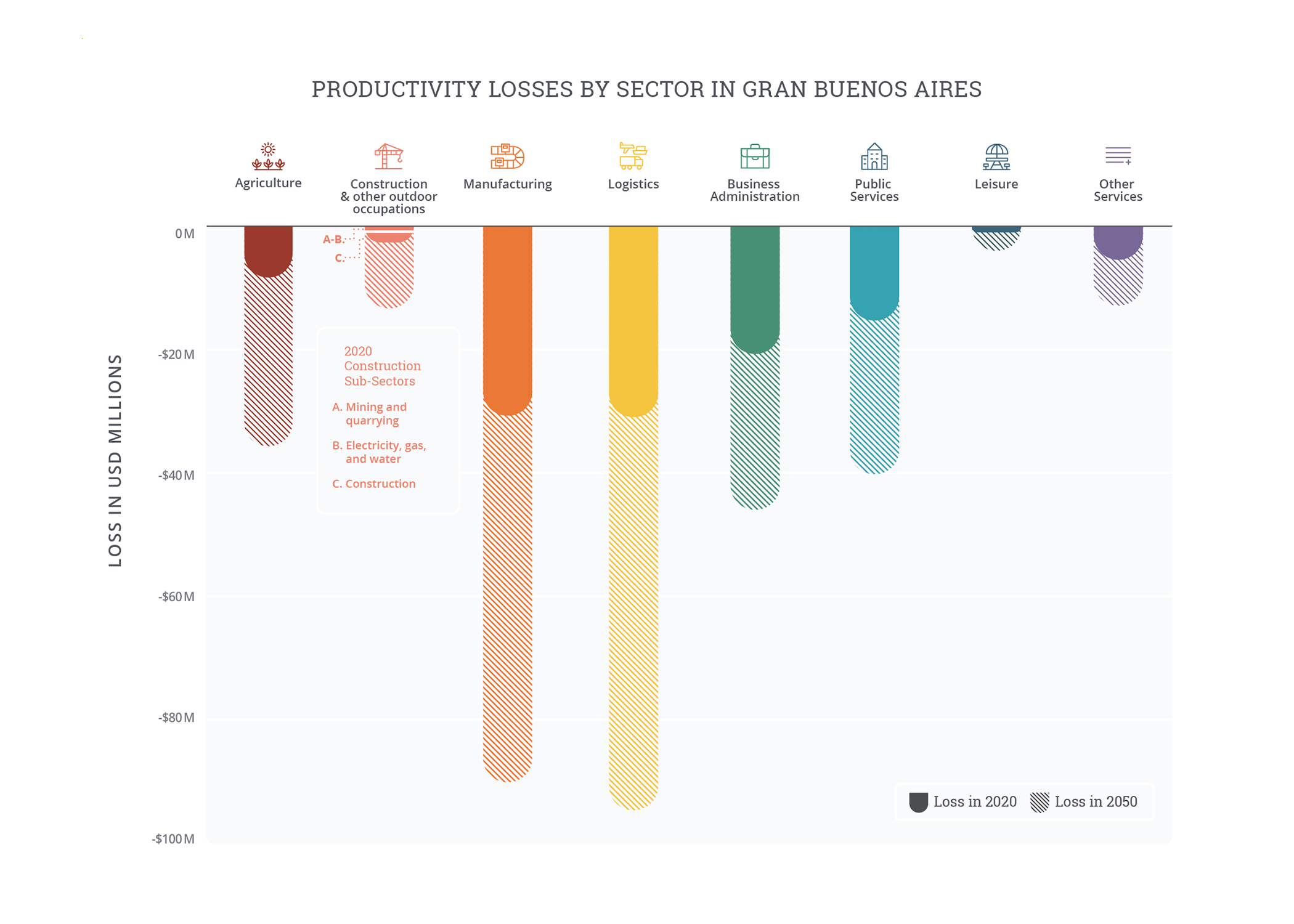

Buenos Aires already loses over USD 115 million (USD 115.02 million/ARS 10,926 million)5 of output in a typical year6 from reduced worker productivity on hot days—and this could triple over the next three decades.7 By 2050, increases in the number and severity of these hot days are expected to double these heat- and humidity-related losses as a share of total output, from 0.2 percent to 0.4 percent.

Under conservative projections of economic growth of 70 percent over the same period, or around 1.8 percent per year, the dollar amount of losses exceeds USD 335 million (USD 336.95 million/ARS 32,006 million). This represents a tripling of lost output in absolute terms and surpasses all climate-related public expenditure in the transport sector across Argentina.8

Buenos Aires already loses $115 million each year because of hot days. This could triple over the next 30 years.

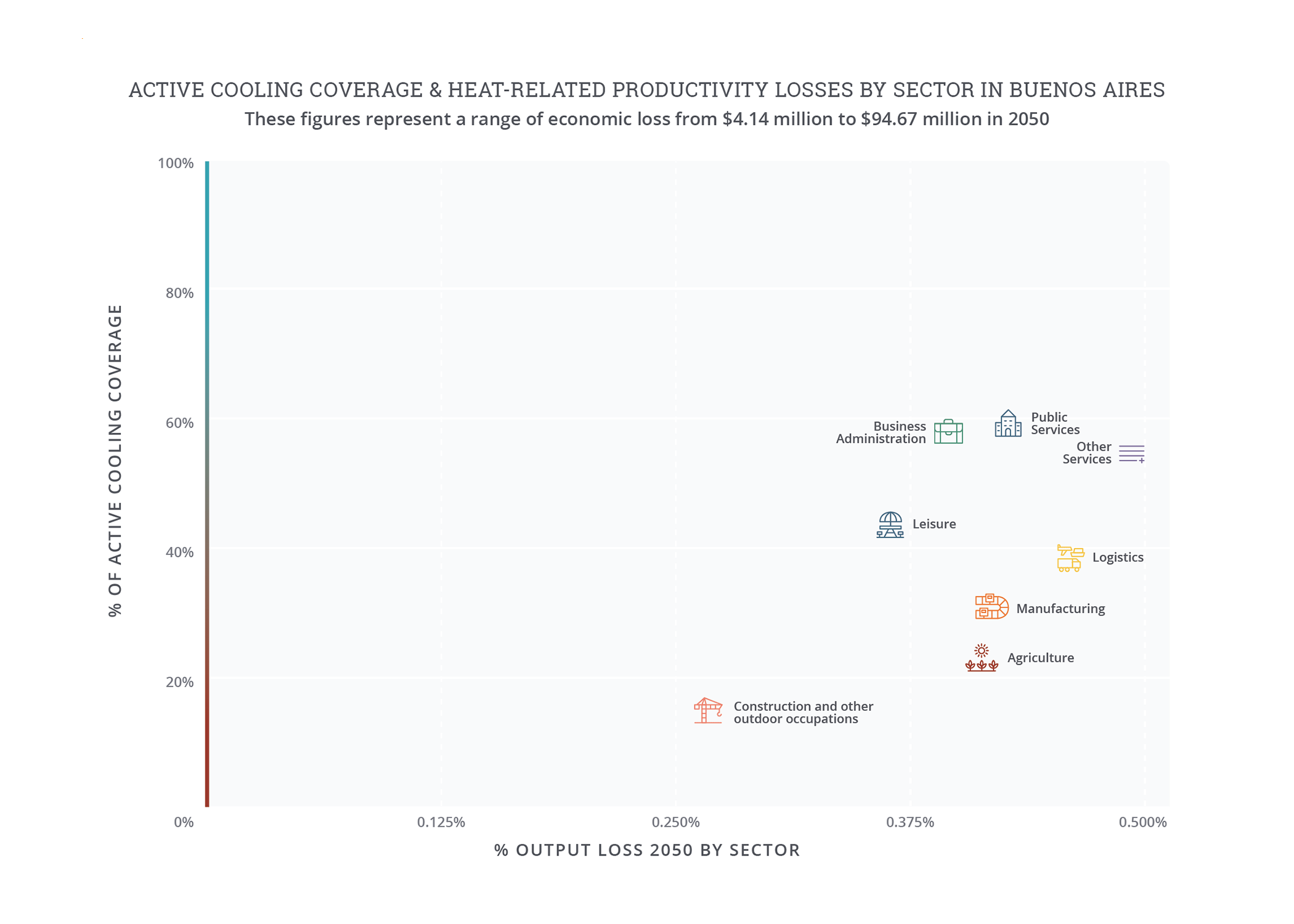

Labor productivity losses are greatest as a proportion of output in manufacturing, trade, and transport services. Greater Buenos Aires’s manufacturing sector, which accounts for 27 percent of output and under current conditions loses an estimated 0.25 percent of its output to heat in a typical year, suffers losses estimated at USD 85 million (ARS 8,074 million) per year. Compared to office-based jobs in business administration or public services, manufacturing requires more physical effort and cooling is estimated to be less prevalent, leaving labor productivity in the manufacturing sector relatively more affected by heat. Logistics, which includes trade from retail to port services, is similarly affected. Business, public services, and other services all enjoy higher levels of air-conditioning penetration, which help their workers to cope with warmer temperatures in the workplace. However, losses reported here cover only direct impacts on worker productivity, and not the broader economic effects caused by consequent reductions to overall demand.

Both income and health impacts of heat on Greater Buenos Aires are expected to be concentrated among its low-income residents, particularly within the informal settlements. Heat-related impacts on mortality and morbidity can already be high—during the 2013 heat wave, daily deaths in Buenos Aires were 43 percent above average at the time9—and without reduced emissions or improved adaptation, heat-related deaths are estimated to escalate by 50 percent by 2050.10 These losses will be particularly concentrated among the 15 percent of the greater metropolitan population who live in informal settlements or “villas”—currently more than two million people, many of whom may be overrepresented in the most heat-exposed occupations, such as logistics and manufacturing. Poverty levels in the villas can be as high as 55 percent, and most households lack access to reliable power sources, limiting their ownership of cooling devices and ability to operate them during hot days.11

Note on “Projected number of hot and extremely hot days”: Days where the twenty-four hour average (i.e., daily) temperature exceeds the local 90th percentile of the baseline average daily temperature are defined as “hot days,” while days where the daily temperature exceeds the local 97.5th percentile are defined as “extreme hot days.” Because hot days are relative to typical local temperatures, the same daily temperature may be considered “hot” in one city but not another. The baseline is based on historical climate data, 1985-2005, while 2050 is based on the 2040-2060 climate projection from an ensemble of CMIP6 models under RCP 7.0. Source: Vivid Economics.

Note on “Productivity losses by sector”: The agricultural sector captures loss within the defined city limits and does not account for agricultural loss from the surrounding rural areas. Baseline losses are based on historical climate data from 1985-2005 and economic data from 2019. 2050 losses are based on the 2040-2060 climate projection from an ensemble of CMIP6 models under RCP 7.0 and economic models under SSP3. Losses assume no change in sectoral composition of economy. Source: Vivid Economics.

Note on “Active cooling coverage and heat related productivity losses by sector”: O*NET, 2021; and analysis by Vivid Economics.

Extreme heat interventions

Buenos Aires can scale up existing programs of action to mitigate heat, ensuring that its most vulnerable residents are protected from rising temperatures. Greater Buenos Aires is taking various adaptation initiatives as part of the Buenos Aires Climate Action Plan:18

- Planning/policy: Private-sector action to increase heat resilience will be encouraged by a buildings code, setting out requirements for solar gain and protection and natural ventilation in new buildings.

- Communications/outreach: Buenos Aires targets vulnerable communities by educating residents on the impact of heat waves, for example through the Adaptation to Extreme Climate Events Program.19 The National Weather Service also provides heat alerts across Argentina.20

- Investment in the built environment and nature-based solutions: Ongoing initiatives include increasing tree cover by more than 20 percent, introducing biocorridors,21 green roofs, walls, and vertical gardens. Other planned activities include improving grid resilience to heat waves by increasing solar photovoltaic generation in residential rooftops to increase supply.22

Explore more city chapters

Return to the global summary

Endnotes

1 To estimate economic losses, this study goes beyond political boundaries to give a sense of how extreme heat and humidity impact Buenos Aries’ influence area. Core economic modeling considers Area Metropolitana de Buenos Aires (AMBA). The regional approach is to ensure that analysis covers populations that are central to Buenos Aires’ growth and urban trajectory.

2 All analysis is based on RCP 7.0 and SSP3 using an ensemble mean of CMIP6 models, with more details available in the accompanying methodology document; to estimate economic losses, models focus on Greater Buenos Aires, although the analysis considers influences and issues relevant to surrounding areas in the broader region. Where data for Greater Buenos Aires is unavailable, we use data from alternative sources. Sectoral gross value added (GVA) shares are scaled to Greater Buenos Aires using the ratio of population.

3 “Caracteristicas climaticas de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires,” Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (website), accessed September 2022, http://www3.smn.gob.ar/serviciosclimaticos/?mod=elclima&id=10.

4 Analysis by Vivid Economics, based on summer average land surface temperature (LST), modeled climate data in 2050, and analysis of expected UHI and urban development from Kangning Huang et al., “Projecting Global Urban Land Expansion and Heat Island Intensification through 2050,” Environmental Research Letters 14, no. 11, 2019, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4b71.

5 Numbers are approximate and rounded to the nearest 10. Exchange rates from International Monetary Fund (2022). 2021 annual average exchange rate – 94.99 ARS/USD. Available at https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61545850.

6 Economic data in this report are from 2019 to avoid capturing the effect of COVID-19 on the economies of the cities analyzed; see methodology for further details.

7 The workability analysis is based on climate factors and not indoor working conditions determined by built environment characteristics or workplace layout (e.g., equipment that generates heat, body heat in close spaces, ventilation or greenhouse effects from windows, external shading). In practice, some of these factors can make indoor environments hotter than the modeled climate conditions suggest.

8 Pamela Ferro et al., “Climate Commitments and National Budgets: Identification and Alignment,” Inter-American Development Bank, Climate Change Division, November 2020, https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Climate-Commitments-and-National-Budgets-Identification-and-Alignment-Case-Studies-of-Argentina-Colombia-Jamaica-Mexico-and-Peru.pdf.

9 BBC, “Heatwave Kills Seven in Argentina,” 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-25564633; and Eric Roston et al., “Killer Heat Forces Cities to Adapt Now or Suffer,” Bloomberg, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-extreme-heat-death-city-adaptation/.

10 Analysis by Vivid Economics, based on heat-mortality vulnerability functions from the C40 Cities benefits tool; see “Resilient Cities: Measuring Benefits of Urban Heat Adaptation,” C40 Cities, 2021, https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Heat-Resilient-Cities-Measuring-benefits-of-urban-heat-adaptation?language=en_US.

11 Ondina Rocca, “Transforming the Heart of Argentina’s Economic and Social Prosperity, Its Cities,” World Bank (blog), February 28, 2017, https://blogs.worldbank.org/latinamerica/transforming-heart-argentina-s-economic-and-social-prosperity-its-cities; and TECHO, “Relevamiento de asentamientos informales,” 2016, ;

12 Puerto Buenos Aires, Reporte de sustentabilidad 2018/2019, 2019, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/web_reportesustentabilidad2018_2019.pdf.

13 Analysis by Vivid Economics, based on summer average land surface temperature (LST), modeled climate data in 2050, and analysis of expected UHI and urban development from Kangning Huang et al., “Projecting Global Urban Land Expansion and Heat Island Intensification through 2050,” Environmental Research Letters 14, no. 11, 2019, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4b71.

14 O. Merk, “The Container Port of Buenos Aires in the Mega-ship Era,” Discussion Paper, International Transport Forum (ITF), 2018, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/buenos-aires-in-mega-ship-era.pdf.

15 ITF, “Container Port Automation: Impacts and Implications,” International Transport Forum Policy Papers, no. 96 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021), https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/container-port-automation.pdf.

16 La Nación, Cuál fue la última ola de calor récord en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires?,” October 27, 2021, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/sociedad/cual-fue-la-ultima-ola-de-calor-record-en-la-ciudad-de-buenos-aires-nid27102021/.

17 Al Jazeera, “‘Another Hellish Day’: Argentina Swelters under Record Heat Wave,” January 14, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/14/argentina-swelters-under-record-heat-wave.

18 Buenos Aires Climate Action Plan 2050, City of Buenos Aires, April 2021, .

19 “Programa de adaptación frente a eventos climáticos extremos,” Buenos Aires Environmental Protection Agency (website), accessed September 2022, .

20 “Olas de calor,” National Weather Service (website), accessed September 2022, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/verano/olas-de-calor.

21 Buenos Aires Climate Action Plan 2050; biocorridors aim to connect large green nodes and incorporate vegetation.

22 The target is 30 percent residential rooftops having solar PV generation by 2050.