Games not only have the potential to change the world for the better, but already do so. Across the world, game developers are leaning into their expertise to make complex topics—like climate change—approachable and even engaging.

Evidence suggests players are eager for more great climate games. We’re here to help you make those games.

This report is a critical resource for the game industry, bringing new qualitative research to bear with a robust examination of current game development practices and approaches.

In this report, you’ll learn how games can be made to drive real-world change, and explore the four main challenges teams have faced when creating their climate games.

This chapter is just one of the challenges outlined in our report Gaming for climate action: The strategy guide for designers, developers, and publishers. In this section, you’ll learn how to balance the reality of climate change knowledge with the importance of engaging and fun game design.

What’s in the report?

Main analysis: Gaming for climate action

Challenge 1: Determining why you want to make a climate game

Challenge 2: Know your practical plan for impact

Challenge 3: Making reality fantastical

Challenge 4: Making your game fun

Making reality fantasical

If a game is not engaging, it does not matter how grounded in reality it may be. Without players, there is no impact. Every game that takes on real-world challenges will have some fantastical elements.

These distinctions from the real-world experience must be a strategic balance to ensure a game can be fun while remaining informative.

Inside the climate game space, the stakes are high. If your game aims to inform players of the early warning signs of heatstroke so that these player communities suffer fewer extreme heat casualties, then it is key to represent accurate signs of heatstroke in the game. Outside of clear-cut learning objectives, however, the trade-offs of accuracy start to get blurry—especially because we know that a perfect simulation of reality is unlikely to capture attention. Games need a perfect mix of fantasy and reality.

In learning from our studied game teams, we have identified a process by which you can weigh these trade-offs while maintaining impact. This challenge is the most complex out of the four this project tackles, and, we believe, the most important. In fact, the tension between facts and fantasy in climate games threads through the other presented challenges.

We must start with a critical question: What can fantasy representations of the world offer us if we want to convey messages or interventions concerning real issues? The answer, it turns out, is quite a lot.

The power of imagination

We can look to Puerto Rico for a recent example of just how powerful imagination can be at scale, even in circumstances where extreme crisis has already taken place.

The collection of Caribbean islands that form the US commonwealth of Puerto Rico are home to over 3 million people, a deep pre-Columbian history, and a rich interwoven culture that integrates traditions from the many peoples that have come to the islands over the centuries. Unfortunately, Puerto Rico is also vulnerable to hurricanes.

On September 7, 2017, Hurricane Irma blasted past Puerto Rico’s main island as a category five storm, tearing local power and water systems apart with heavy rain and wind.

Only thirteen days later, Hurricane Maria brutally slammed directly into Puerto Rico. Roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals were severely damaged, 97 percent of roads became impassable, and 95 percent of residents lost access to drinking water.

Researchers at Arizona State University (ASU) have charted out how this transformed imagination evolved, transitioning from a scramble for survival to a hope-filled drive for a better future. These researchers determined that imagination directly enabled transformation.²

The story they tell goes like this: solar-powered distributed electrical grids would represent a more sustainable, more resilient energy system for the people of Puerto Rico. After all, the entire grid cannot fail at once if solar power can feed into micro grids across the islands. Environmental reporter Brian Kahn wrote a story for Gizmodo asking whether the disaster might allow the island communities an opportunity to reimagine and rebuild such a solar-powered energy grid. Sustainability advocate Scott Stapf posted a link to the story on X (then known as Twitter), directly tagging Elon Musk, asking him if he wanted to rebuild Puerto Rico’s electricity system with his solar and battery systems. Musk replied that he could if the people of Puerto Rico wanted him to, and Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló, replied within hours that Puerto Rico could be a flagship project for Musk’s Tesla.

While Tesla moved quickly, arriving within weeks with equipment and expertise to set up solar-powered grids, both Musk and his company’s interest soon vanished. As they encountered the type of challenges inherent in any major infrastructure project, they abandoned plans and materials. The Cuidad Dorada senior center site demonstrates how this overall project went. When engineers attached panels and batteries to the existing old electrical wiring, the batteries blew out. A nurse at the senior center said, “It doesn’t work. It never did.”

While Musk may have not followed through, his public exchange with the Puerto Rican governor thrust the idea that such transformation was possible into the mainstream.³ Major publications took the notion of a resilient solar energy future seriously. The New York Times, the Washington Post, PBS, NPR, the BBC and more media featured detailed pieces, interviews, and segments examining what might be possible. This media attention, in turn, inspired local groups and individuals to act quickly.

One Puerto Rican teen, Salvador Gómez-Colón, delivered solar lamps to over three thousand five hundred households. The local social movement Queremos Sol brought together residents, activists, engineers, and nonprofits to develop a road map toward rooftop power on every Puerto Rican home. As a result of this organizing, small solar systems were installed on dozens of homes in critical areas, and hundreds of systems were installed to power fire stations, hospitals, and schools. One resident said their new solar power made them “feel more secure, if we get another big hurricane like Maria, I won’t suffer so much.”

The ASU researchers spent two years interviewing Puerto Ricans across the islands to determine just how resilient solar-powered energy systems moved from vague dreams to actual transformational change. The key, they concluded, was the emergence of something called a sociotechnical imaginary—a shared hope, imagination, and vision of the future, where a new way of living is reflected in the design of collective scientific and technical projects.⁴ Powered by shared experiences and widespread discourse, this imaginary persuasively spread across the residents, organizers, decision makers, and policy makers of Puerto Rico, leading to complimentary actions at the local, community, commonwealth, and federal levels.

It is crucial to understand that one of the reasons Puerto Rico’s new, resilient solar-powered imaginary is so successful is that it is not monolithic.⁵ While the shared hope and vision for the future is widespread, this imaginary has room for local communities to adopt and adapt it to fit their specific circumstances. One low-income community trained volunteers to install solar battery systems and organized a group buying strategy, bringing down installation costs so much that 30 percent of households in this community now own solar systems. Another community leveraged solar power to ensure the local water system would be less vulnerable to grid outages. A third community saw local businesses pool resources to adopt solar battery systems, with a pledge to use the money saved on their energy bills to fund solar systems for low-income neighbors. A fourth community saw clusters of homes come together to purchase shared solar battery systems where individual households would not be able to afford one for themselves.

Change happens when a powerful shared goal is paired with the recognition that there will be many paths toward that goal. Imagination powers social transformation when it is both widespread and flexible enough to be reinterpreted, and inflexible solutions will never be capable of powering the type of transformation needed for environmental sustainability and climate resiliency.

As the ASU researchers write, existing solar companies did not have business models or logistical processes that fit most of Puerto Ricans’ needs, as they generally had targeted larger businesses or wealthier clients. Public policy and financial institutions had no mechanisms ready to support Puerto Rico’s solar transformation, having favored standardized energy rollouts or utility-scale power plants above diversified bottom-up solutions. In the wake of Hurricane Maria, these existing institutions failed Puerto Rico’s people. Tesla failed. The people of Puerto Rico, empowered by their new shared imagination for what was possible, found a multitude of solutions. In the twelve months following Hurricane Maria, solar adoption in Puerto Rico had nearly doubled.

By learning from Puerto Rico’s story, we can see that ultimately even public policy can be shaped by the shared imagination and efforts of people working hard to change their lives and their world for the better. This is a story about what a community was able to achieve despite a high-profile failed effort, and despite a critical lack of federal support in the midst and wake of a humanitarian crisis. Even though the promise of Musk’s philanthropic support turned out to be a fantasy, Puerto Rican communities collectively reclaimed this fantasy as their own and worked to turn it, bit by bit, into reality. A shared, hopeful imagination of a better future paved the way toward real, resilient, adaptable, and diversified progress.

Still, it would be better to generate powerful imaginaries without any shared experience of disaster. Luckily, both past research and our discussions with game developers for this project cement games as one of the most powerful tools for building imaginaries we have. Games often deliver powerfully realized fantasies which invite players to immerse themselves within them, interact with them, learn about them, dream about them, and form communities around them. When designed with intention and care, these fantasies can meaningfully connect back to real-world transformations, and, crucially, allow players to chart their own path through challenges. Games can provide a method of co-creating resilient, hopeful imaginaries of a better future in a healthy context—so long as they are designed with this intent in mind, balancing fantastical and realistic representations carefully.

The fantasy of free parking

Game developers think about fantasy all the time—across genres and target audiences. As Insomniac’s Spider-Man 2 creative director Bryan Intihar told Jen Glennon at Inverse, decisions are made specifically to reinforce the target fantasy. “There’s a reason the [Insomniac Spider-Man] games open up with swinging right away,” he said. “That’s the ultimate fantasy.”

As great games draw us in, they help us reimagine what this fantasy might feel like, and help the fantasy feel real. Games can leave lasting impressions on us because these experiences are more specifically real than we had been capable of imagining on our own. Sometimes we discover that these experiences are different than we had imagined in surprising ways. Players come to games for the fantasy they imagine they want, but often stay for the fantasy the game offers.

Nearly every single development decision impacts how a project defines the line between imagination and reality. What decisions can a player make in a game? What systems do we ask them to think about? What environments do we offer to them to explore? How are we presenting these environments?

There are no definitive right or wrong answers to any of these questions. Whether you are making a game to help players laugh with delight, think critically, or build a lasting player community, you have to make these decisions. Games are always abstractions of the rest of our world, filtered through the people who make them. One of the best ways to see how this can work is to look at games that balance fantasy and reality in interesting ways, even if unintentionally. The creative intent behind 2013’s Sim City was not climate or environmental messaging, but the game does illustrate a collision between imagination and real contexts well.

The game was set in real, US urban centers. However, and rather famously in retrospect, this game about cities doesn’t include parking lots.

Sim City Lead Designer Stone Librande admitted that when the team went out to survey local cities to better ground the game’s design, they were shocked to discover how much space was taken up by parking lots. “We were originally just going to model real cities, but we quickly realized there were way too many parking lots in the real world and that our game was going to be really boring if it was proportional in terms of parking lots,” he explained.

The design team decided to imagine that almost all parking was underground in their game, ultimately putting token parking spaces on the side of the largest buildings. “We had to do the best we could do and still make the game look attractive,” Librande explained.

This was a choice made in response to the grounding reality of the game being different than what the developers had imagined it would be. It is also a choice about what an “attractive” city can look like.

Sim City was not a project that was interested in disrupting this fantasy. But what if it had been? What if a city in Sim City looked the way car-oriented cities actually do, instead of the way the developers imagined such cities to look before they researched for their game? What if the game presented pedestrian-friendly urban spaces as the way to achieve a more attractive urban aesthetic?

If these different choices had been made, then, perhaps, the imaginary that players would encounter in the game might challenge their expectations, and this surprising difference might engage players to uncover more surprises within the game’s systems and presentation. Through this feedback loop, players could develop and internalize entirely new imaginaries of how urban areas work.

As Benjamin Abraham has argued, the game ARMA 3 is a great example of how a novel imaginary might be embedded in a game. While the game presents itself as a grounded military combat simulation game, it also just happens to take place in a future that has already grappled with climate change. As Abraham writes, the “gameplay’s backdrop is a future in which a full-scale transition to renewable energy in domestic power generation has already occurred…. [T]he game actually presents in some sense a politically optimistic vision of the future.” Fossil fuels do not exist in the grounded simulation of ARMA 3. The game confidently expresses that a green transition is part of a realistic look toward the future, as players navigate solar and wind farms during play sessions.

One of the climate game project leads expressed this to us:

“Games have the unique ability to get people thinking about interesting issues. It was a big goal for us with our game to do exactly that: create an environment where people are exploring interesting topics and sort of pushing themselves a little bit intellectually without knowing they are. And so that’s always a big goal for games that we make. It’s just sort of sneaking in that level of thoughtfulness.”

Different approaches to finding balance

While there are a number of different methods to build a deliberate imaginary, clear patterns emerged across the surveyed games.

Often, climate game developers mused that the “cozy” game genre and its prioritized sense of safety, abundance, and softness may have grown as a natural response to the COVID-19 pandemic and worsening climate impacts. When the world can feel overwhelming, these types of games can act as a refuge. Perhaps, many of our participants said, this also means that cozy games can engage players around the otherwise uncomfortable topics of climate and environmental impacts and interventions. By committing to non-overwhelming presentations of overwhelming problems, more players might feel comfortable participating. On an aesthetic level, cozier representations of uncomfortable contexts might help shape people’s mental models and imaginations.

One interviewee spoke specifically about the challenges of honestly presenting the dark themes of climate impacts through a genuinely hopeful and human-centered lens. The game needed to position people and their collective actions at the center of an optimistic vision for the future without falling back on aesthetics that reinforced defeatist outlooks.

It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever really had to do as a creative director for a game.

However, they also acknowledged that the more they navigated this balance of honest optimism, the more comfortable they became with the process.

Beyond broad aesthetic considerations, teams also put a lot of thought into how they defined and scoped their intended contexts. Climate change interventions generally sit at the intersection of environmental, technical, and social contexts. For example, Puerto Rico’s solar transformation saw local communities come together (a social context) to find new ways to build solar battery infrastructure (a technical context) to adapt to worsening extreme weather events (an environmental context). Climate game projects have tended to focus on one or two of these contexts at a time, with the understanding that effective impact would be easier to achieve with a more focused scope.

Projects focused on eco-technical contexts found it important to dedicate high-level project goals to accurate representations of core concepts, and then support the team across disciplines as they learned new ways of working to integrate this knowledge. For example, one team had come to their new climate game project from a project with a pure fantasy setting. The team was familiar with a creative process where they had conceptualized and generated flora from scratch. This team needed time and training to develop a new research-based approach to support the climate game’s commitment to representing a specific real-world environment.

Projects focusing on social and cultural contexts needed to take special care as well. Often, the stakes can feel higher. We make games to be played by people we hope to connect with. The emotional stakes of representing a species of tree or an exact formula for carbon conversion are always going to be lower than the emotional stakes of representing real people’s realities and building new imaginaries from those realities.

One game director spoke with us about the care they’re taking with their game’s setting, given the context of how their setting is often negatively portrayed in the media. “When you see [our city] in movies and games all you see is police, drug dealers, violence, guns, right? They focus on like 3 percent of [our city], not the 97 percent of people that are just trying to make it. I don’t want to ignore the fact that there’s bad things happening, or pretend it’s some kind of utopia, but I don’t want [players] to get the impression that everyone is bad either,” the game director said.

The team is in constant conversation with people who live in the subject community to ensure the representation is as genuine and inclusive as possible. The development process was thoughtfully structured to implement changes based on community feedback. Because of this feedback loop, even before the game is released, the team knows that their representation matches their intent. “I had one guy come up to me literally in tears saying, ‘Thank you for giving us a solid representation,’” the game director continued. “[Someone else told us], ‘I got tingly feelings when I saw the trailer. It reminded me of when I grew up there.’”

Another director reinforced how intentional they are about treating their real-world setting with care. To change negative perceptions, one method they use is to base the game’s characters on real people. “They’re people who want to be in the game, who want to get their voices and all their experiences [represented] in a way that they’re happy with,” the director explained. “We [developers] almost want to step out of the way and let people have their stories told.”

Still, we heard from climate game developers that representation efforts cannot simply use other people’s stories as content—especially when the game itself serves a for-profit purpose. Unfortunately, Western media has a problematic history of paying people in the so-called Global South or from underrepresented cultures only for the time it takes to relay stories and experiences—and then the media entity will claim it legally owns these stories and experiences as its own intellectual property. We heard from developers in the Global South that they still personally see this happening. (Martin Scorsese’s 2023 film Killers of the Flower Moon, about the 1920s murders of the Native American Osage people, spawned many reflective pieces on this dynamic. This specific film arguably represents real progress while also highlighting the wider progress that is still needed.)

Developers proposed a few tactics to balance the inherent power of highlighting generally unheard voices to a global audience of players with a just treatment of represented communities.

First, of course, there are opportunities to expand the resources and support developers within these communities can access and utilize. These communities are already creating in response to climate impacts, expressing cathartic stories in their games, and envisioning new hopeful futures to strive toward. These teams have historically been overlooked by traditional game investment and publishing structures, and could use additional recognition and support. As we examined in our section on Challenge 2, Jiwe is an example of a studio and platform that aims to address some of these gaps from the bottom up.

Second, when a game team is working with a specific community, teams suggested structures that ensured that the community would benefit from earned funds as long as the game itself could drive business.

Again, all of these efforts to meaningfully and respectfully integrate real contexts into a game project add complexity and new challenges to the project, which no teams took lightly. Different teams approached this extra workload in different ways. Some leveraged mainstream narrative approaches and existing imaginaries as a shorthand to communicate with the player, rather than embarking on extensive research. While this might be a dangerous approach to use where common assumptions might be misleading, we also saw how teams were thinking carefully about the level of specificity their players would need to understand. For example, one team realized that they were not interested in making a game about the intricate causes and effects of deforestation, but definitely wanted players to realize deforestation is happening and is harmful. “There is a forest and then there are people cutting down trees. And then there is no forest. For that kind of narrative, we didn’t need to create a huge research base,” one team lead pointed out.

Another game director said that they asked trusted subject matter experts to let them know what effective interventions looked like, and were able to represent many of these interventions without taking on additional research internally. These experts often sourced through relevant NGOs (including Arsht-Rock), universities, and even social media.

Other teams carved out time for internal research. One director spoke with us about their team’s more self-directed “20 percent time” While there is certainly no mandate to spend that time researching climate justice topics, “I do [spend time researching], and my hope is that other people in the team feel inspired. And I share my knowledge with the team, and they share theirs.”

Across all of the climate game teams we spoke with, we saw a clear pattern that teams with access to relevant specialized expertise had an easier time making deliberate decisions around how to represent their real-world contexts in-game. Nearly all of the teams we spoke with wished they had more expert support. We heard a desire for expertise around climate impacts, mitigation, and adaptation, alongside expertise on biology, ecology, and design for change. Several teams attempted to fill these gaps on an informal basis by leveraging experts that team members personally knew or experts that might already exist in their player communities. Other teams recruited experts from academia, social media, or community organizations, finding people who could speak personally to the contexts portrayed in the game.

While many climate game teams of the past and present have done an impressive job of integrating these additional research processes into their game development pipelines, it is clear that teams wish it were easier to identify and include the right experts in their processes—people who both know what they are talking about, and also have time to help a game studio as they figure out how best to communicate with audiences. Another critical gap in resourcing quickly became evident as we started to notice how many projects were able to leverage asset stores during their development process—along with which projects couldn’t.

If I’m trying to build New York City in a game, I can find those assets pretty fast online. But if I’m trying to build anywhere in Africa, I literally have to build [assets] from scratch.

From landscapes to architecture to plant life, asset stores like the Unity Asset Store and the Unreal Marketplace simply do not yet include many locations from across the world, which means climate game teams have more trouble if they want to represent these locations. Additional support for marketplace assets that represent those areas most affected by climate change would go a long way toward filling this gap and enabling new games about and for these impacted areas.

With the right mix of resources, access to expertise, and processes, game teams can consciously and deliberately balance the interplay between fantasy and reality in their projects. These resulting games are then able to shape and co-create new imaginaries with their players, and thus are capable of making significant contributions toward a better world.

Diving into Daybreak

Daybreak, designed by Matt Leacock and Matteo Menapace and published by CMYK, is a “cooperative board game about stopping climate change. It presents a hopeful vision of the near future, where you get to build the mind-blowing technologies and resilient societies we need to save the planet.”

Helpfully, the designers have written extensive, publicly available design diaries examining their processes, decisions, and iterations throughout the development of this game. The focused care and attention they paid to the challenge of creating a mass-market game about climate change began from the moment they identified their key goals for the project. These goals included centering play around systemic interventions to carbon emissions and integrating real-world data so that players could “viscerally experience” emissions and their actual consequences. Ultimately, they wanted players to feel empowered whether they had won or lost. Their goal was for players to appreciate that reversing global warming represents an incredibly difficult challenge, and also that such a reversal is possible through decisive cooperative action.

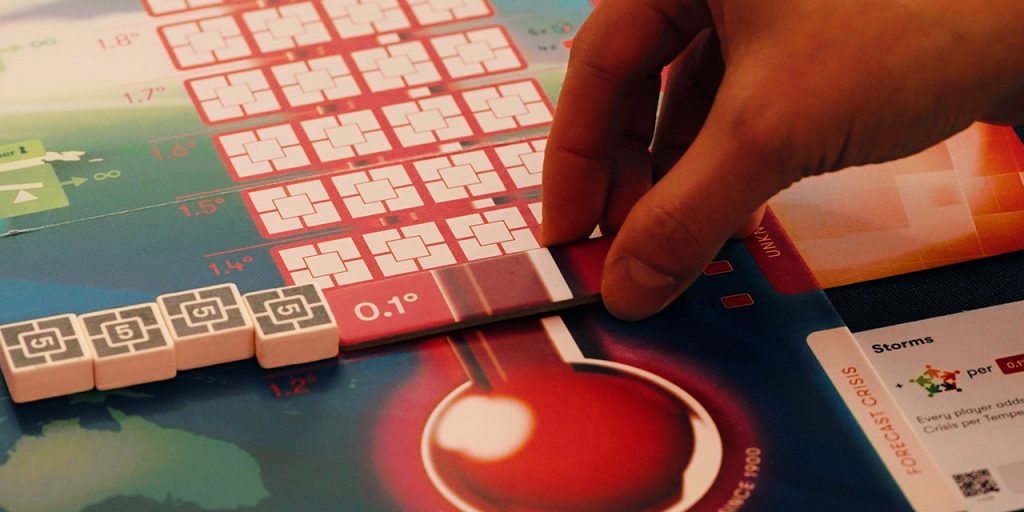

With these goals set, the designers decided that before they could ever hope to create gameplay around systemic climate change interventions, they would need to translate the hard science of the carbon cycle in a way that felt realistic without being overwhelming to players. Initial attempts at a game board modeled carbon emissions retained in the atmosphere and captured by forests and oceans, alongwith planetary changes such as melting ice caps and creeping desertification. This work quickly revealed some of the unintended consequences of framing global warming using some traditional game design methods, as counters and trackers triggered unhelpful mental models in playtesters regarding both how long a game session might take and what failure might represent.

As Menapace writes, “The world won’t end in 2050 or if global warming reaches 2.0 degrees Celsius. Therefore, a loss should happen if players lose control of the system,” rather than at an arbitrary data point cutoff. Still, the game needed to instill a sense of urgency, so the game was changed to use rounds to define the amount of time players have to address global warming within the scope of the game. Leacock and Menapace tweaked and iterated on every system and interaction in the game to create an imagined reality that conferred the necessary mental model in players. They knew they wanted every 0.1 degree Celsius of warming to feel important, so they charted out a system where players could see impending effects coming and experience consequences at temperature tipping points. Through playtesting, they noticed that abstractions like “financial capital” and “political power” were not landing emotionally, and so they pivoted to representations that centered the human cost of climate impacts. They added gameplay so that players could implement climate-resilient policies to shield vulnerable people from the worst effects of climate disasters. They then further refined their language, and the game began referring to “communities” instead of “people” in order to highlight the scale and interconnected nature of climate impacts. Here, the designers were carefully moving in-game representations slightly away from the fantasy of simplified abstraction and toward a grounded realism.

Sometimes iterations moved in the opposite direction, toward fantasy, in service of an overall balance between fantastical abstraction and reality. Early versions of the game featured extensive climate crisis forecasting systems, offering players the chance to discuss which types of impacts were impending and take early steps to ward them off. While this modeled how climate action can involve forecasting in reality, the designers found that this system threw too much information at players, and so players consistently ignored it altogether. So, they refined the system to a single preview of an impending crisis per round; forecasting was given just enough of a presence to enter players’ imagination, but no longer required an overwhelming amount of attention or processing.

With every iteration, Daybreak’s designers stepped closer to creating an experience that met their goals. The game’s ability to impact players is defined by the quality of the reflective, extensive, ethnographically detailed playtest process they used, but it also required a strong, specific clarity of intent. From top to bottom, Leacock, Menapace, and Daybreak’s publishing team CMYK (run by Alex Hague) worked together to leave players with a specific new notion: there is no one way to solve the climate crisis. All interventions are challenging, but it is worth daring to imagine that change is possible. Leacock ends his final design diary with an expression of a hopeful imaginary using a quote from author Octavia E. Butler: “There’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers—at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.”

Daybreak’s very vision acknowledges that there is no single correct response to the climate crisis. This does not weaken its vision, nor does it represent a lack of specificity to the interventions presented by the game. As we saw in Puerto Rico, communities drove a variety of contextually specific, bottom-up actions. It is the specific combination of a shared vision paired with a flexibility of paths toward that future that ultimately unlocks powerful, widespread transformation.

For both game creators and players, climate games can help us confront the gaps between where we are and where we imagine we want to go. They can help us concretely imagine what is possible, what is useful, and what has meaning. They can help us chart a multitude of paths through the challenges we face. Games can do all of this without necessarily requiring us to experience the worst of climate impacts first. While imagination can sometimes be dismissed as a silly distraction, we can see in the field of sociotechnical imaginaries research that imagination is an innately powerful force embedded in the human experience. All games need to do to leverage this force is to carefully consider how and why they’re balancing fantasy and reality in their representation of the world.

Leacock and Menapace’s design diaries remain a treasure trove of generously documented expert climate game design, full of reflections and concrete examples of how the game evolved through its iterations. Now, we will leverage their reflections to examine the final major challenge that all climate game projects must face: How on earth do you make a climate game fun?

Keep reading the report chapters

Main report page

Gaming for climate action: The strategy guide for designers, developers, and publishers

This report provides a strategy for designers, developers and publishers to develop games that inspire and spur climate action.

Challenge #1

Determining why you want to make a climate game

This report chapter covers the ways climate themes emerge in the game development process.

Challenge #2

Know your practical plan for social impact in the game

This report chapter covers the ways climate games are currently designing for impact both within and around their core play experiences.

Challenge #4

Making your game fun with climate game design

This report chapter addresses the challenge of making a game with climate or environmental themes enjoyable for players.

Citations

- ¹ Nishant Kishore et al., “Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria,” New England Journal of Medicine 379: 162-170, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972.

- ² Angel Echevarria et al., “Unleashing Sociotechnical Imaginaries to Advance Just and Sustainable Energy Transitions: The Case of Solar Energy in Puerto Rico” IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 4 (3): 255–268, doi: 10.1109/TTS.2022.3191542.

- ³ Echevarria et al., “Unleashing Sociotechnical Imaginaries.”

- ⁴ Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim, “Sociotechnical Imaginaries and National Energy Policies,” Science as Culture 22 (2): 189–196, https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2013.786990.

- ⁵ Echevarria et al., “Unleashing Sociotechnical Imaginaries.”

About the challenge

This chapter is part of a larger report on “Gaming for climate action: The strategy guide for designers, developers, and publishers.” The report identifies four key challenges that sit between a climate game project and its success.

About the authors

Trevin York is the founder and director of Dire Lark, a game design for change studio in Edinburgh, Scotland. With fourteen years of experience leading game projects, York organizes Game Developers Conference’s Climate Workshop, is a co-author of the International Game Developers Association’s Environmental Game Design Playbook, and is a senior fellow at Arsht-Rock.

Catherine-Ann McNamara-Peach is an anthropologist and PhD candidate at the London School of Economics. Her research studies theories of change in UK climate activism and the existential and relational challenges of life in the Anthropocene. She is interested in the potential of the cultural sector to shape social imaginaries around multi-scalar climate responses.

Ariadne Myrivili is a game designer with a focus on team management, how leadership impacts design, the intentions of design, and how design effects players. She is currently working on projects centered around games’ ability to turn global events into digestible narratives to improve public response and engagement.

Seb Chaloner designed the visual assets for the report. He is a graphic designer, visual artist, and design researcher. His current work explores how diffuse design, ArtScience, and cultural probing techniques can facilitate communities to become active in mitigating the biodiversity crisis. Seb is also a lecturer at the School of Arts & Creative Industries, Edinburgh Napier University, with a focus on active learning rather than preaching from a podium.

Special thanks to: Sam Alfred, Carlos Coronado, Paula Escuadra, Elena Höge, Max Musau, Grant Shonkwiler, and Clayton Whittle as well as the Arsht-Rock team, especially Jessica Dabrowski, Kathleen Euler, and Kashvi Ajitsaria.

Our methodology

This report is a critical resource for the game industry, bringing qualitative research to bear with a robust examination of actual development practices. The research was conducted by a multidisciplinary team that deeply understood both game development and research. To learn more about their methodology, click here.