Games not only have the potential to change the world for the better, but already do so. Across the world, game developers are leaning into their expertise to make complex topics—like climate change—approachable and even engaging.

Evidence suggests players are eager for more great climate games. We’re here to help you make those games.

This report is a critical resource for the game industry, bringing new qualitative research to bear with a robust examination of current game development practices and approaches.

In this report, you’ll learn how games can be made to drive real-world change, and explore the four main challenges teams have faced when creating their climate games.

This chapter covers just one of the challenges outlined in our report Gaming for climate action: The strategy guide for designers, developers, and publishers. In this section, you’ll learn how to find the fun in your climate game project.

What’s in the report?

Main analysis: Gaming for climate action

Challenge 1: Determining why you want to make a climate game

Challenge 2: Know your practical plan for impact

Challenge 3: Making reality fantastical

Challenge 4: Making your game fun

Making your climate game fun

Nearly everyone we spoke with agreed: it can be challenging to make a game with climate or environmental themes fun, but this is a challenge that must be taken on.

Though there is no singular definition of “fun,” our research will consider it to encompass all these experiences that encourage continued, willing, positive engagement from players. “[Games] have to be super fun because otherwise the message won’t reach anyone,” explained one game designer. “It’s better to make a fun game that is commercially successful rather than just an impactful game,” said another.

Finding the fun in any game project takes work. But climate games face an additional challenge. Games that take on scientific approaches or existential despair face a more complicated process to retain players’ attention and participation.

The way through this challenge is to intentionally integrate your chosen subject matter into gameplay. As teams integrated their contexts into their very fabric of fun, they consistently uncovered interesting, innovative, and engaging new game systems and features.

From math to emotion

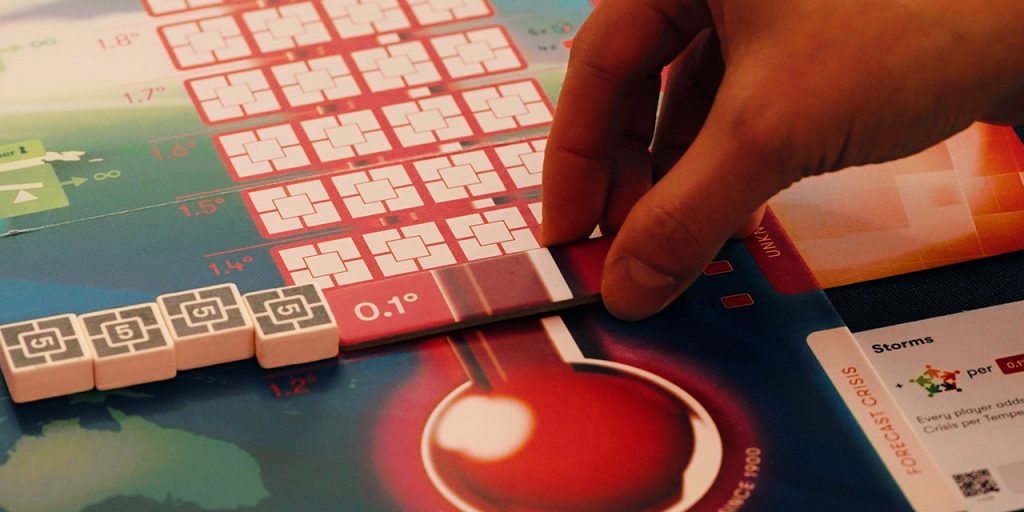

“Playable does not automatically mean fun,” writes Menapace in the second design diary for Daybreak. When the team playtested Daybreak, they uncovered a problem with the rules around converting carbon emissions to global temperature increases. While the relationship between emissions, temperature, and consequences was central to the game, the implementation relied on a simple mathematical operation. Emissions tokens were divided by the number of players to determine the temperature increase. It turned out that players really did not want to be asked to do division as a regular part of gameplay, and they often made mistakes as a result.

This mathematical operation had a second problem: one of the game’s scientific advisers pointed out that it was significantly flawed. Instead of abstracting a real system into a form that was simplified and approachable, the Daybreak designers had ended up portraying the relationship between emissions and global temperature in an actively misleading manner. When the game asked players to turn emissions counters into temperature counters using division, players understood that the current global temperature is determined by the current level of emissions.

However, this is far from the truth. Global temperatures are instead driven by the concentration of greenhouse gases from past emissions. Reducing new emissions is essential, but it would be misleading to suggest that reduced emissions would quickly lead to reduced global temperatures; the existing concentrations of greenhouse gases would also need to be reduced.

Menapace and Leacock solved both their science communication problem and their fun problem by critically considering two questions at once:

- What exactly about the relationship between emissions and global temperatures is most important to communicate?

- Where in this system lies the most potential for compelling gameplay?

Where gameplay can offer meaningful choices to players, the game can and should ask players to think carefully about their actions. In all other cases, the game should provide the most direct communication possible.

The designers ended up removing the emissions conversion calculation completely. Emissions tokens are instead added directly to a thermometer, simulating the way that new emissions are added to existing concentrations to drive global warming.

The designers focused their efforts to engage players with meaningful choices and better understand the consequences of this global warming. Through iterations, playtests, and contributions from CMYK’s Alex Hague and Justin Vickers, the team arrived at a system where the consequences of each degree of heat felt significant and sobering. The emotional and attentional weight of this system had successfully been shifted away from a procedural mathematical process and placed instead on the heart of the game: What are the consequences of the climate crisis, and what are we going to do about it?

Reinvention within Terra Nil

“Making your game environmentally themed is not the hard part,” Sam Alfred told us in an interview for this project. “It’s getting people to play your game that’s the hard part.” Alfred was the lead designer and lead programmer on Terra Nil, “an intricate environmental strategy game about transforming a barren wasteland into a thriving, balanced ecosystem” developed by Free Lives and published by Devolver Digital. As he told us, the game’s presentation of ecosystem restoration within the genre of strategy gameplay caused significant challenges; conventional gameplay mechanics often found in the strategy genre were directly at odds with Terra Nil’s core themes.

“If there’s a single piece at Terra Nil’s core that we refused to budge on, it’s the idea that nature has intrinsic value. It is not valuable for what it can give you, it is valuable because of its very existence,” said Alfred. Several classic strategy game mechanics had to be discarded to remain true to this idea. “We spoke at early stages about [using] the forest to construct some buildings out of natural materials. Then we decided, no, because then you’re chopping down the forest and the forest becomes a resource.”

Traditional resource extraction mechanics just wouldn’t fit in this game. Neither would continuous expansion or land colonization. “These mechanics aren’t inherently bad or wrong [for other projects],” Alfred explained, but Terra Nil would not be able to express its themes if its gameplay contradicted them. The game’s genre would have to be deconstructed and reconstructed in order to find fun that aligned with the game’s themes.

By confronting and working through these challenges and remaining committed to their themes, however, the team was able to find truly innovative approaches to their chosen genre. Part of the confidence required to embrace this challenge among the team stemmed from the positive feedback the project’s prototype had already received. As Alfred shared during his Game Developers Conference session, Terra Nil started its life as a Ludum Dare original protype. The theme of that year’s game jam was “start with nothing.” Participating projects were developed and submitted over 48 hours under that theme. Alfred decided to use a literal interpretation and set his prototype in a barren wasteland. He wanted to pair city builder and strategy mechanics with environmental themes, so that “instead of building a city, you were building an ecosystem.”

As Alfred told us, he had no grand plan to make a game with a message, necessarily. Instead, he reflected, this project is an expression of what’s important to him. “Being in touch with the natural world is very much a part of South Africa’s national heritage. The natural environment around us is very important to us, and we have incredible natural parks and I’ve spent a lot of my life hiking all over the country. This is close to my heart,” he explained.

Alfred understood that if he and the rest of the team could figure out how to make a good game and inspire a deeper connection with the natural world among players at the same time, then that would be a game worth making.

The Ludum Dare prototype already featured the heart of what would become Terra Nil. Players used a combination of tools including wind power, toxin scrubbers, and rewilding to bring a biodiverse ecosystem back to the starting wasteland. This prototype received a positive response from the Ludum Dare audience, and, importantly, it continued to receive positive feedback in the months that followed. As Alfred continued to develop this prototype over the next year, a surprisingly significant number of players were moved to make donations to the prototype even though it was available for free download—more than Alfred has ever seen for a free game. He attributes this unique response to the prototype’s ability to connect with players. Other players wrote long articles online about what this prototype meant to them. This meant that as the team expanded the prototype into a full game, they already knew what resonated with players. The team turned to regular playtesting and community engagement to make sure the experience still retained that resonance.

For Alfred, the process of learning how to integrate natural systems into compelling gameplay is only going to pay dividends in the future. He was excited to share elements of environmental restoration he had learned during the development of Terra Nil which ultimately did not fit into the project. “I’ve always been a mechanically minded designer,” he said, “but learning about these things, these elements of the natural world, and being immersed in this space… will definitely influence my projects going forward.”

Key support makes finding fun easier

When we asked participants to reflect on what might have made their lives easier as they learned to weave their chosen contexts and topics into compelling gameplay, two notable patterns emerged.

First, in a theme that echoes our earlier discussions around the ways multidisciplinary institutional experience can facilitate work, experienced game designers generally have an easier time navigating the deconstruction and reconstruction of traditional game systems, mechanics, and genres. Game design is a craft, and that craft is usefully applied even when transferred to the slightly new context of climate game design. We heard stories from experienced game directors and designers that have shown climate game project management becomes easier with experience. We also heard from teams that struggled to navigate these challenges until they managed to identify and hire an experienced designer. Second, and a little less obvious than “hire experienced designers,” we heard many participants tell us their team benefited from experts who were specifically focused on helping the team navigate many of the challenges laid out in this report—experts deeply familiar with both game development and subject matters.

One project lead expressed it to us like this: “We want to [hear] from experts. [Experts who can say,] ‘Yes, I understand the research. I understand games. Your concept is good enough to marry the two.’… Or, ‘change a word in here,’ or, ‘no, this isn’t going to work, and actually it promotes a bad message; either scrap it or rework it’…. Subject matter-related developer relations is probably a good way of thinking about it.”

Another participant told us, “We essentially had a huge panel of advisers and supporters that we could always lean on to get their thoughts on the way that we were doing something…. I think it kept us just really honest in the game because there were a lot of people looking over our shoulder, checking our work, thankfully.”

Participants who had access to this type of support shared these stories with a tone of gratitude and relief. This type of expert support eased the burden on the game development team to figure out everything from scratch, and helped the team identify design dead ends and mistakes before they used up too many development resources. This type of support could also give teams the confidence to pursue innovative ideas. With the experience and validation from those who think about climate game design or climate communication challenges, developers were able to better use their time and resources.

The teams who received this support valued it highly, wanted more of it, and hoped to use this type of support earlier in future projects. A potential stumbling block here is that there are not many established systems to deliver this sort of specialized design and development support to the projects that could benefit from it. Many teams had trouble finding this support, ended up finding it too late for their current projects, or did not find it at all. The number of people and institutions currently qualified to offer this support is also still rather limited.

Still, progress is being made. As more climate games are released, more developers are learning how to navigate these challenges, and with enough experience, some of these developers may be able to aid others. Arsht-Rock is currently trialing different models of support here, too, with the inaugural Climate Games Launchpad accelerator pairing funding, mentorship, and expert support together for participating teams. We recommend identifying sources of expert support as early as possible for your project, ideally before you require it, so that you’re able to leverage it when you need it.

Keep reading the report chapters

Read the report

Gaming for climate action: The strategy guide for designers, developers, and publishers

This report provides a strategy for designers, developers and publishers to develop games that inspire and spur climate action.

Challenge #1

Determining why you want to make a climate game

This report chapter covers the ways climate themes emerge in the game development process.

Challenge #2

Know your practical plan for social impact in the game

This report chapter covers the ways climate games are currently designing for impact both within and around their core play experiences.

Challenge #3

Making reality fantastical in climate change games

This report chapter delves into how fantasy representations of the world can convey real-world messages or interventions.

Explore more

About the challenge

This chapter is part of a larger report on “Gaming for climate action: The strategy guide for designers, developers, and publishers.” The report identifies four key challenges that sit between a climate game project and its success.

About the authors

Trevin York is the founder and director of Dire Lark, a game design for change studio in Edinburgh, Scotland. With fourteen years of experience leading game projects, York organizes Game Developers Conference’s Climate Workshop, is a co-author of the International Game Developers Association’s Environmental Game Design Playbook, and is a senior fellow at Arsht-Rock.

Catherine-Ann McNamara-Peach is an anthropologist and PhD candidate at the London School of Economics. Her research studies theories of change in UK climate activism and the existential and relational challenges of life in the Anthropocene. She is interested in the potential of the cultural sector to shape social imaginaries around multi-scalar climate responses.

Ariadne Myrivili is a game designer with a focus on team management, how leadership impacts design, the intentions of design, and how design effects players. She is currently working on projects centered around games’ ability to turn global events into digestible narratives to improve public response and engagement.

Seb Chaloner designed the visual assets for the report. He is a graphic designer, visual artist, and design researcher. His current work explores how diffuse design, ArtScience, and cultural probing techniques can facilitate communities to become active in mitigating the biodiversity crisis. Seb is also a lecturer at the School of Arts & Creative Industries, Edinburgh Napier University, with a focus on active learning rather than preaching from a podium.

Special thanks to: Sam Alfred, Carlos Coronado, Paula Escuadra, Elena Höge, Max Musau, Grant Shonkwiler, and Clayton Whittle as well as the Arsht-Rock team, especially Jessica Dabrowski, Kathleen Euler, and Kashvi Ajitsaria.

Our methodology

This report is a critical resource for the game industry, bringing qualitative research to bear with a robust examination of actual development practices. The research was conducted by a multidisciplinary team that deeply understood both game development and research. To learn more about their methodology, click here.