Seville’s battle with extreme heat

The beginning

The planet is getting hotter, and that puts Seville in a perilous position. With a population of 1.5 million, it is the hottest urban area its size (or larger) in Europe. In the summer months, Seville frequently has daily maximum temperatures exceeding 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit). As elsewhere, this extreme heat can be deadly.

Against this backdrop, in 2021, Arsht Rock reached out to the administration of Seville’s then-mayor, Juan Espadas, with an idea: Would the city government be interested in partnering with Arsht-Rock to protect people from extreme heat with a health-based heat early warning system? This system, built using decades of local meteorological and mortality data, had been tested in other cities, and could eventually be integrated into the existing heat warning system operated by AEMET, Spain’s national weather service.

Like most places, AEMET’s warnings are based only on weather readings. But some national weather services are beginning to incorporate health-based metrics to inform their warning systems, acknowledging that the same weather can have a different impact depending on local conditions and the timing of a heat wave. Arsht-Rock’s system offers a low-resource, health-based approach, using historical data on excess mortality correlated with meteorological data. This additional perspective on the potential impacts of extreme heat events on people’s health and well-being, can complement or improve upon other warning systems and make them more relevant for public and individual decision-making.

City officials in Seville were intrigued by the idea. They also liked Arsht-Rock’s proposal for publicizing the most extreme heat events – naming them, like hurricanes are named, as a novel way to raise awareness of dangerous heat. This additional publicity could trigger people to take countermeasures and thus save lives. Espadas and the Seville City Council adopted and co-created the local implementation of the pilot, and in the summer of 2022, Seville not only launched the new categorization system; it became the first city in the world to name a heat wave.

A new way of predicting the impact of extreme heat

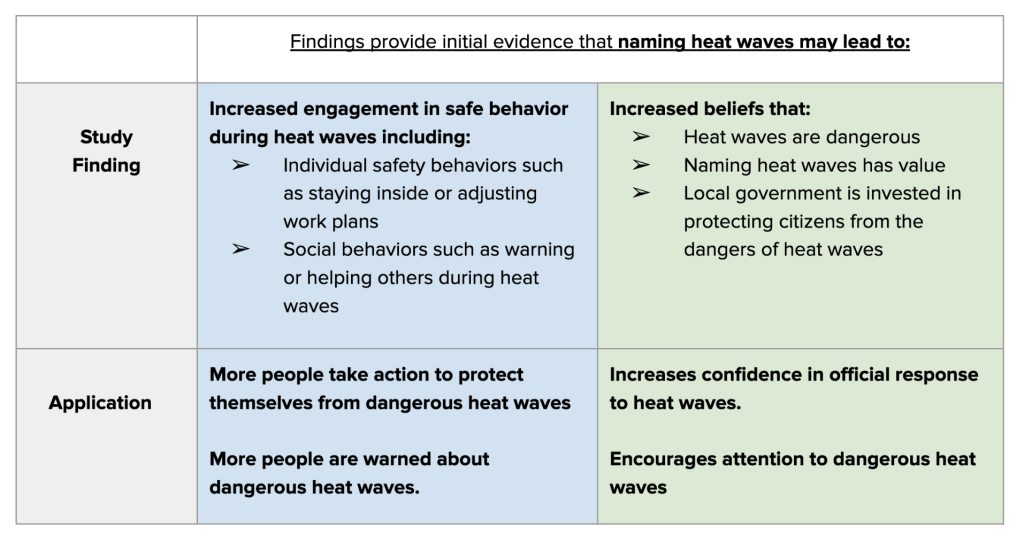

Arsht-Rock partnered with Climatologist Laurence Kalkstein, Arsht-Rock’s chief heat science advisor, to develop the system and to identify thresholds for Arsht-Rock’s additive idea of naming the most severe categories of heat waves. This built off the work of Kalkstein and his colleague Scott Sheridan, who had been working on regional health-based heat warning systems since the 1990s. Their model, versions of which had been used in Philadelphia and other cities in the United States, was then reviewed and revised by Arsht-Rock’s Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance (EHRA), a collection of over 60 global expert organizations and scientists in public health, finance, humanitarian assistance, disaster management, climate science, insurance and public infrastructure brought together by Arsht-Rock, to test and improve the model with experts. The result was our health-based early warning system to categorize and name heat waves.

The system is based on how the factors that make heat waves more dangerous–such as air temperatures, dew point (related to humidity), sea level pressure, cloud cover–contribute to negative health impacts over time for the population of a given region. Kalkstein, Sheridan, and their team of researchers examine decades of both historic weather conditions and all-cause mortality data to analyze what type of conditions are associated with excess mortality in the region. That analysis is then used to create an algorithm for predicting the likelihood of excess mortality based on certain weather conditions. This means including variables beyond temperature, such as how abruptly the temperature rises, how much it differs from seasonal norms, and how well the population has tolerated those extremes in the past. Clusters of days can then be categorized based on estimated mortality, and early warnings can be issued to the public and city health and emergency responders.

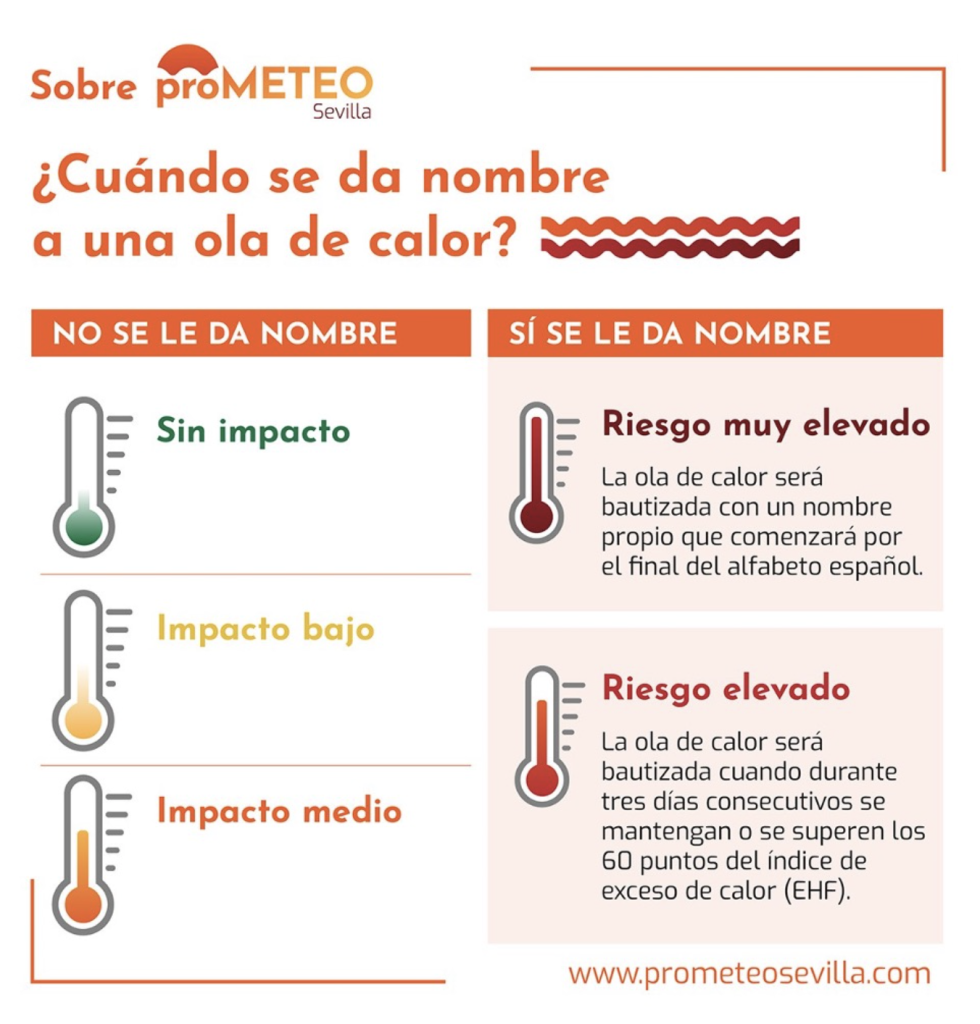

With the system in place, heat waves expected to have the most extreme negative health impact can be named and publicized to raise additional awareness – though naming is not an essential element of categorization. In 2022, six cities tested Arsht-Rock’s health-based early warning system to categorize heat waves. Only Seville deployed a heat wave naming protocol.

The Seville model

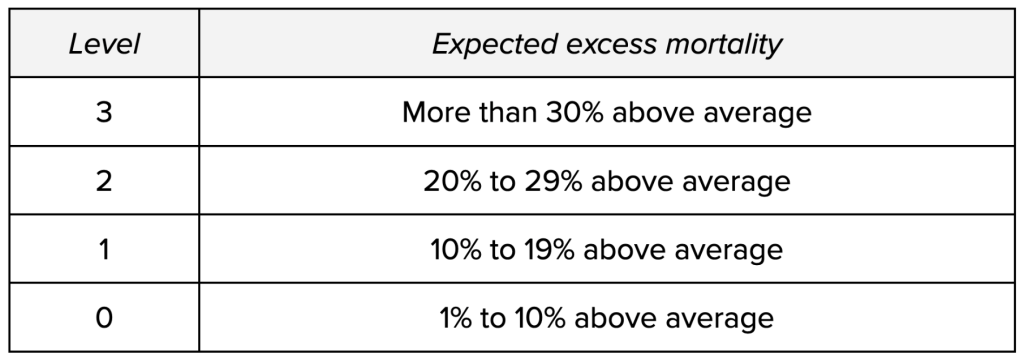

Seville’s health-based categorization system used four categories, scaled zero to three. Three or more consecutive days of high heat at the zero and one categories were classified as “heat events,” while those at categories two and three were described as “heat waves.” Each category represented a projected increase in excess mortality of ten percent, as shown below.

Arsht-Rock and the Seville City Council enlisted the help of Descubre, a Seville-based communications agency, to build a modest local communication effort. As summer approached, Descubre worked to create a brand, outreach materials, website and social media presence for the pilot, as well as a media strategy to get some attention for the pilot project’s launch and the naming and categorization calls. Arsht-Rock and their social marketing contractor, Marketing for Change Co., collaborated closely with Descubre providing content as well as creative guidance and technical assistance.

Based on the feedback from local focus groups, a series of thermometers were selected to visually represent the four-level categorization system and common Spanish names were chosen for naming the most dangerous heat waves. The team also settled on a name for the pilot—proMETEO—a reference to Prometheus, the Greek god of fire, combined with the Spanish word “meteorologia”.

The pilot was run in close communication with the Andalusian office of the Spanish weather service, AEMET. While AEMET continued to issue warnings based on its own existing heat warning system, the pilot gave AEMET and others a chance to see what our model might add to that system.

The pilot officially launched June 20 – the eve of the first day of summer – with a press event that pulled together an impressive turnout of the city leaders. In addition to the mayor and Arsht-Rock leadership, press conference speakers included the director of the Spanish Office for Climate Change (Valvanera Ulargui), AEMET’s Andalusian meteorologist (Luis Fernando López Cotín), and the director of the Infrastructure Secretariat of the University of Seville (Victoria Domínguez Ruiz).

Along with our health-based early warning system, the first three possible heat wave names were announced. The event immediately generated 35 local print and digital stories, two television packages, and four radio pieces, Descubre reported.

The heat arrives

It didn’t take long for the system to be tested. Forecasts for early in July showed conditions approaching the high end of Category 2 range, hot enough for 20 percent to 29 percent excess mortality in the Seville model. José María Martín-Olalla, Associate Professor, Department of Condensed Matter, Sevilla University and the technical expert selected by the Seville proMETEO partners, served as the local scientific lead for the project. Looking just at the forecast, he felt the heat wave would likely be “borderline” in terms of naming. Since no heat wave had ever been named, debate emerged over whether to name this one based on a “borderline” forecast: “The thing is that if you start making too many warnings, then the system becomes kind of useless,” Martín-Olalla noted later, “People are like ‘Okay, this is just another warning.’”

As forecasts turned into reality, “it was kind of two or three days of very intense decision-making calls [and] emails” across continents and time zones, Martín-Olalla recalled. The 10-day heat wave passed through unnamed, but the close call clarified roles and decision points across the Seville implementation team and the Arsht-Rock support team— just as piloting an idea is supposed to do.

The world’s first named heat wave: “Zoe”

It didn’t take long for that clarity to be tested. About a week later, forecasts predicted a second, somewhat more intense heat wave that appeared likely to become a Category 2 or even 3. This time, with everyone more certain about the criteria, their roles and the severity of the forecast, Martín-Olalla recommended the heat wave get a name, and the city agreed. Heat Wave Zoe Sevilla—a Category 3 heat wave that lasted from July 22 to 27—became the world’s first named heat wave.

A retrospective look at the summer activity on those channels, using the social listening platform Infegy, showed a total of 140 posts mentioning both Zoe and the word heat wave (in English or Spanish), resulting in 37,500 impressions reaching about 6 million people. The greatest spike of posts occurred the week of July 24 with 88 posts generating 808 engagements.

The potential to improve today’s warnings

By the end of summer on September 23, the pilot’s health-based categorization system had ranked four heat events or heat waves of Category 1 or above; the first, a Category 1 heat event, arrived June 11 before the proMETEO campaign launch later that month. The second, a Category 2, was the heat wave that arrived July 9 and was not named. Zoe, a Category 3 heat wave, was the third. A final Category 1 heat event began the last day of July and lasted 4 days. The occurrence of four heat events or heat waves was an increase from 2021, which had a single heat wave (a Category 3 in August), but was just below half the 25-year average of nine heat events or heat waves a summer.

Our health-based early warning system to categorize and name heat waves identified two heat waves that did not generate warnings from AEMET. This suggests that warning systems that include analysis of excess mortality, such as our system provides, may capture potentially dangerous heat impacts that meteorological-only systems may miss.

Gauging the impact on the public

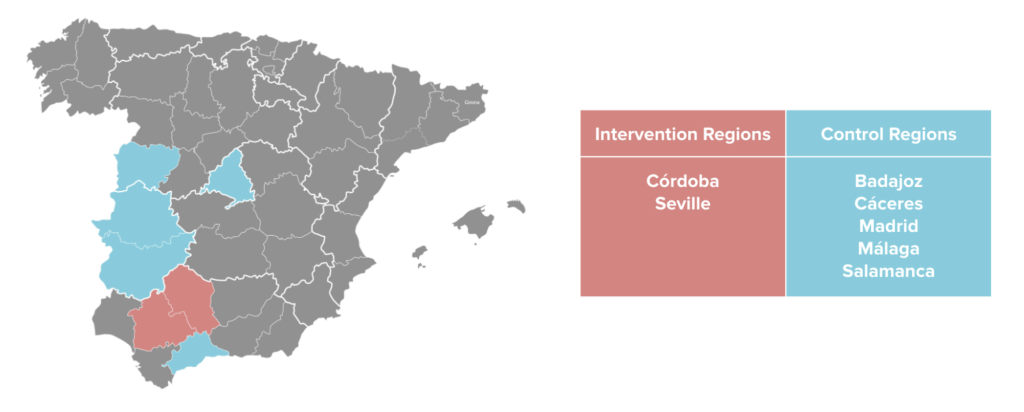

After the summer came to a close, Arsht-Rock examined the pilot’s impact in a post-intervention survey (n=2,052) conducted from September 23 through October 7. The sample was split: 738 respondents were from the provinces of Sevilla and Córdoba, a rough approximation of the local media market; the other 1,314 were from five other areas farther away but with similar climates (Badajoz, Cáceres, Madrid, Málaga and Salamanca).

It had been two months since Heat Wave Zoe Sevilla, but the survey measured a significant amount of awareness, especially for a one-time event and given the absence of any paid media. Respondents were asked if they recalled any heat waves that received names. About half the sample did and were asked what the heat wave was named. Six percent of the overall sample, and seven percent of the local media market, recalled the name Zoe unaided. What’s more, most of those who could not recall the name at first affirmed they did remember Zoe when prompted with the name. The combined level of awareness overall—aided and unaided—was 32 percent, roughly a third of the survey’s overall sample.

Gauging awareness of the categorization system was more challenging, in part because people can easily conflate the new Arsht-Rock health-based heat early warning system with the AEMET weather service’s long-established ones. When asked if they recalled any heat waves “categorized by level of severity,” 8 in 10 respondents said they did. But in a follow-up multiple-choice question that asked them whether the categories were 0-1, A-C or 0-3, half of that 80 percent said they could not remember, and the others were relatively evenly split between the three possibilities (two of which were wrong). AEMET uses a color system – consisting of green, yellow, and orange – to issue weather advisories to the public, but does not categorize them using a numerical system.

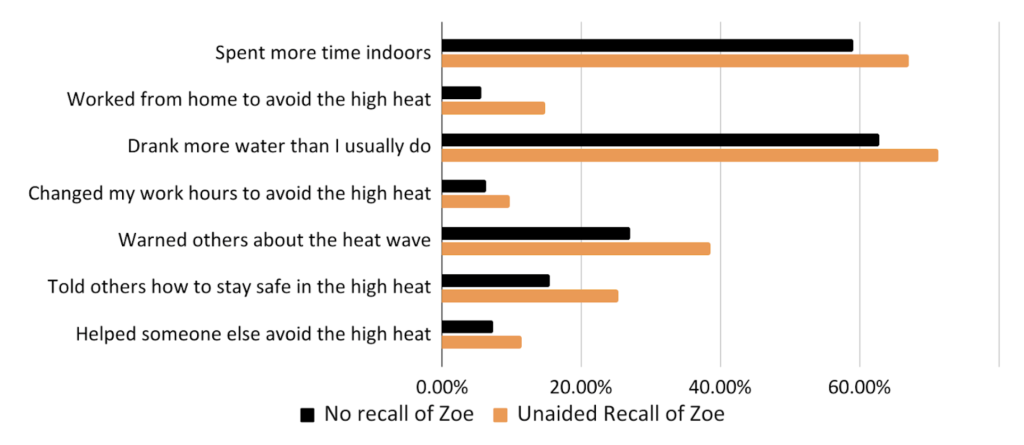

The ability to remember Heat Wave Zoe Sevilla without any assistance revealed a significant link between awareness and behavior, with potentially life saving implications. Statistical analyses compared engagement in specific heat wave safety behaviors that reduce the negative impact of extreme heat of those who recalled Heat Wave Zoe (unaided) to those who did not (see Figure 2). Participants who recalled the name Zoe were more likely to spend time indoors and drink more water. It was also associated with more adjustments to work schedules and location to lessen their exposure to extreme heat. Finally, participants who recalled Zoe were also more likely to engage in prosocial heat wave safety activities, including warning others about heat waves or telling others how to stay safe during times of extreme heat. There were no significant differences related to Zoe recall for other measured heat wave behaviors (for example, changing leisure plans to avoid the heat). But there were also no correlations going in the wrong direction, where those who recalled Zoe were less likely to do safer behaviors.

Several attitudes, including behavioral predictors such as subjective norms, also differed based on this proxy measure of intervention exposure. Participants who recalled the name Zoe were significantly more likely to agree that other people alter their routines during heat waves. Those who recalled Zoe were also more likely to endorse heat wave naming and agree that their local government was effectively working to protect them from heat waves.

A lasting impact and a foundation to build upon

Overall, the naming and ranking effort in Seville undeniably drew attention. Two months after Heat Wave Zoe Sevilla took place, 7 percent of those surveyed in the local media market were still able to recall the name unaided– a figure that extrapolates to 73,000 people in Sevilla and Córdoba. These were people more likely to both protect themselves and warn others. What is not yet clear is whether this correlation is causation. A future campaign, with a greater investment in exposure and a comparison region, would help test that, showing whether an increase in dosage would also lead to an increase in safer behaviors and supportive attitudes.

The pilot also established both the viability of our health-based early warning system to categorize and name heat waves and its ability to add value to AEMET’s current warning system. Our system identified two heat waves that did not generate warnings from AEMET–warnings that could help keep more people safe.

As the Seville pilot now moves into its second year, Arsht-Rock and local implementation partners will be looking to build on this foundation as well as the good will established with the city of Seville. Plans are being made to increase people’s exposure to the warnings and any named heat waves, and improve the impact and notoriety of the project’s calls-to-action. Working with the city to engage emergency response and public health and safety stakeholder systems, including hospitals, government and nongovernment agencies, and community groups, will be essential to reaching populations that are more vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat. Improved communications and response will allow for a more definitive picture of the intervention’s potential impact on the public’s behavior. What’s more, the city may integrate our system and its resulting alerts into other city services. Seville will continue to be a trail blazer, demonstrating how a health-based early warning system to categorize and name heat waves can be leveraged to make an entire region more resilient to climate change.