Overview

Bangkok faces high and rising temperatures: over one month in a typical year already sees daily average temperatures near 30°C.

Heat in Bangkok is already entering unbearable levels, and without global action to tackle climate change, these hot days are projected to increase by 50 percent by 2050.

Heat and humidity are a major drag on worker productivity, causing overall losses valued at 5 percent of output in a typical year, or USD 8.6 billion (THB 293 billion). Without action to reduce emissions or adapt to the changing climate, heat- and humidity-related labor productivity losses could reach USD almost 16 billion (USD 15.6 billion/THB 532 billion) by 2050, or 6 percent of total economic output and a value equivalent to a quarter of pre-pandemic tourist spending across all of Thailand.

Losses fall most heavily in lower paid sectors, with outdoor workers losing as much as 40 percent of output. Extreme heat is also a major contributor to energy poverty, with heat driving energy consumption and bills to contribute to more than 11 percent of household spending.

Bangkok has some worker protection laws in place to manage heat exposure. Further plans for climate action present an opportunity for more ambitious regulation and investment.

Outdoor workers in informal occupations such as motorbike drivers may already lose nearly one-third of their productive working hours to heat stress, forcing them to choose between their income and their safety.

Impact of extreme heat

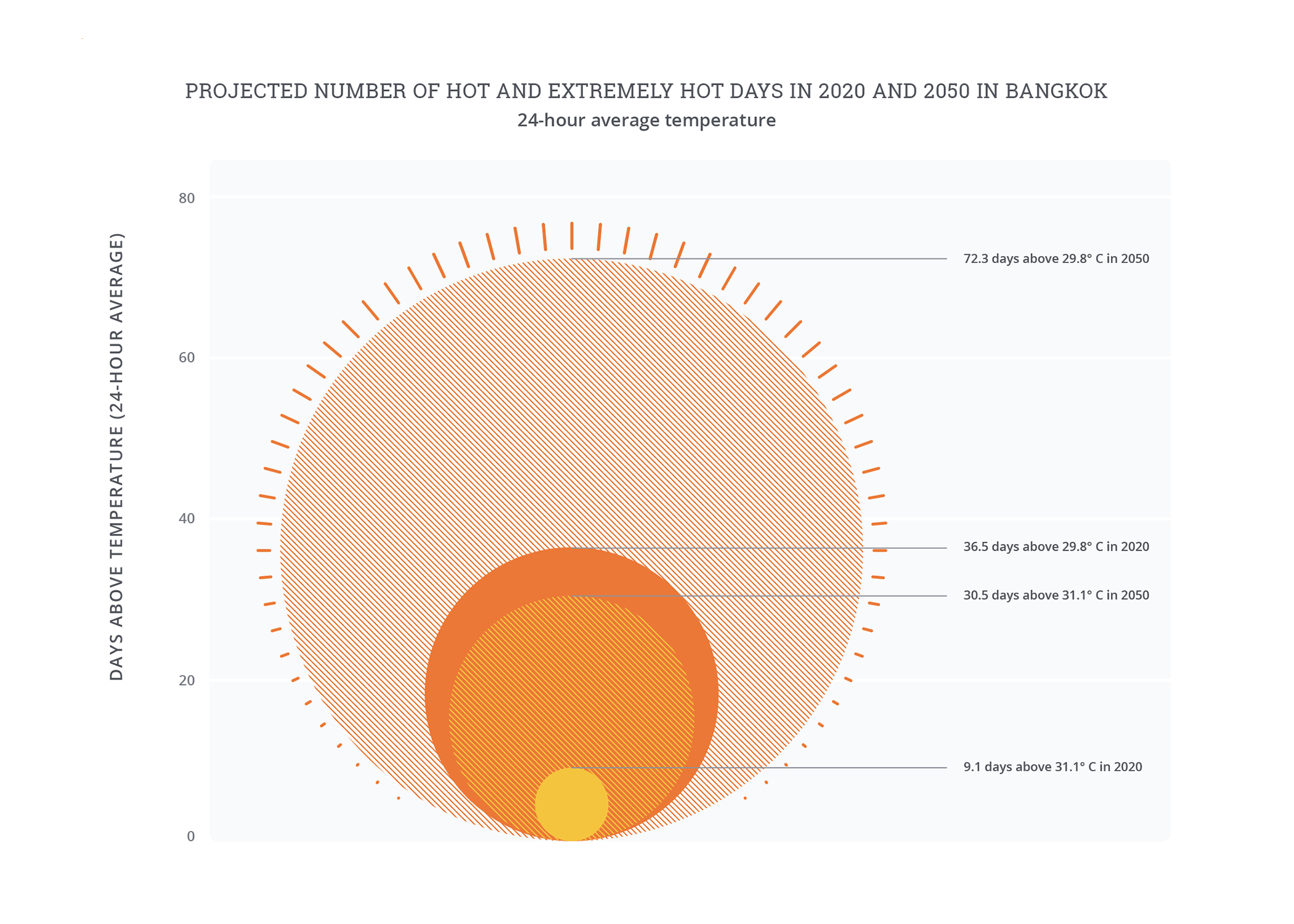

Bangkok1 faces high and increasing temperatures: the city faces 24-hour average temperatures near 30°C for almost one month in a typical year, and these high temperatures may be experienced for forty-two days in a typical year by 2050.2 In part due to low urban green-space ratios (3.3 square meters of green space per person, compared to a global benchmark of 9 square meters3), the city is subject to a strong urban heat island (UHI) effect—with summer land surface temperatures in the city 10°C higher on average than surrounding countryside.4

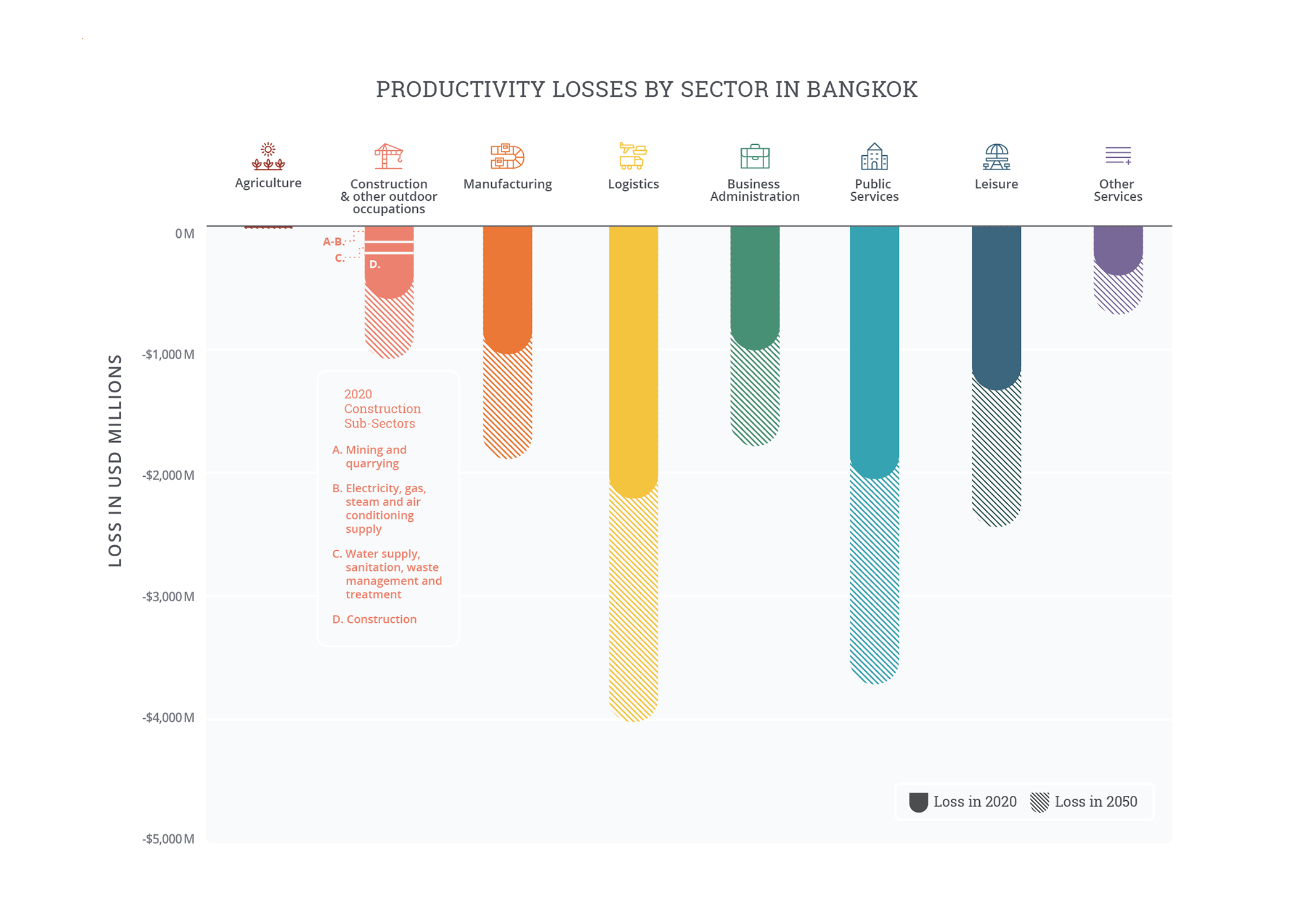

Heat and humidity are a major drag on worker productivity, causing overall losses valued at 5 percent of output in a typical year.5 In absolute terms, overall lost output due to heat- and humidity-related reductions to labor productivity amounted to over USD 8 billion (USD 8.6 billion/THB 293 billion6) in a typical year around 20207 and, without emissions reduction or adaptation, are projected to rise to over USD 15 billion (USD 15.6 billion/THB 532 billion), or 6 percent of output by 2050. This is equivalent to nearly one-quarter of total international tourist spending in Thailand in 2019: USD 61.6 billion (THB 2.1 trillion).8 These losses capture the direct effects of heat and humidity on economic output, but do not capture any knock-on effects as lower wages and output result in lower spending and reduced demand in the economy at large, even for sectors with less heat exposure in their working conditions.

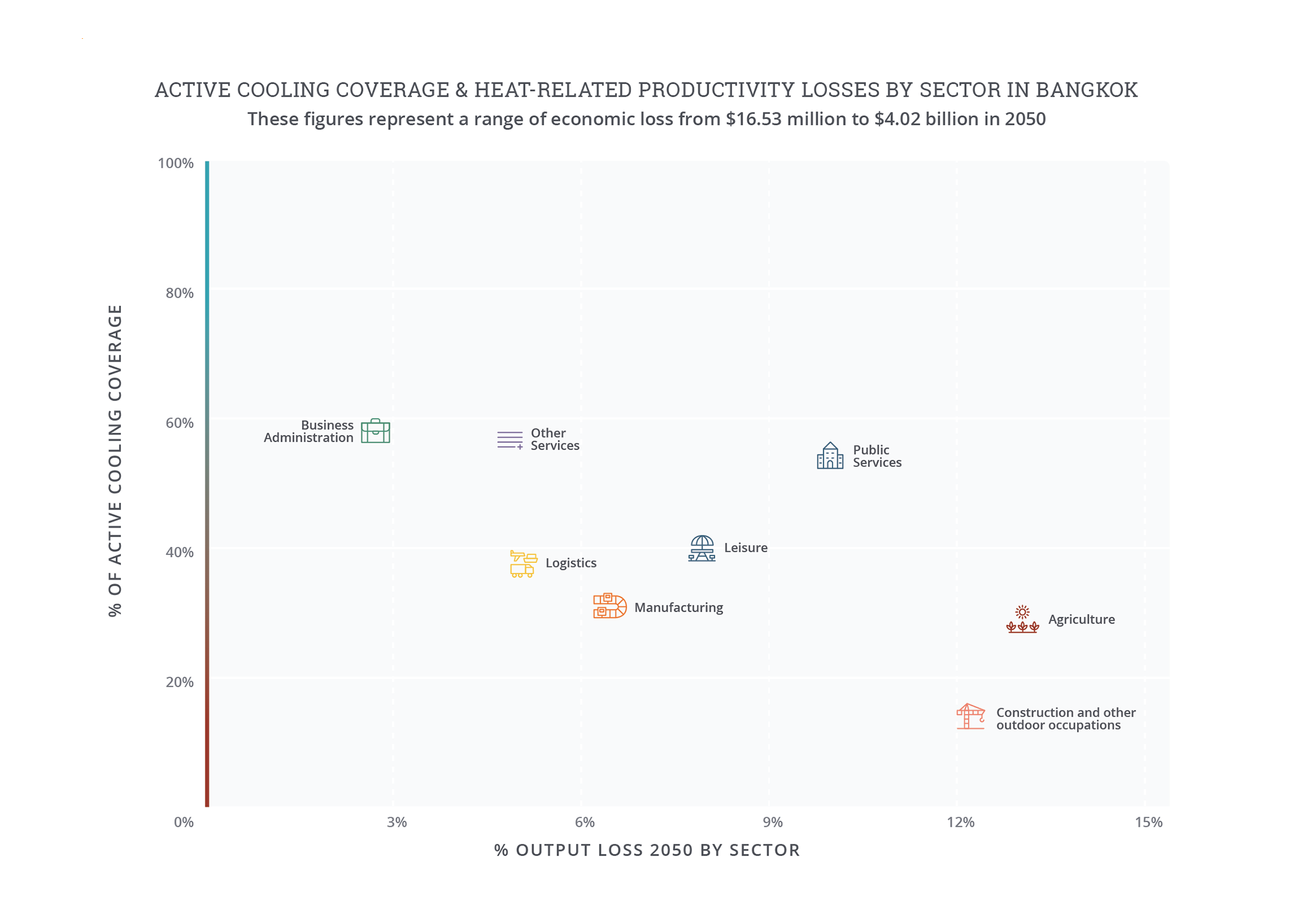

Losses fall most heavily in lower paid sectors, with outdoor workers losing as much as 40 percent of total economic output. A quarter of losses (around USD 2.2 billion, or THB 70 billion in 2020) are currently in logistics, including transport and trade. Outdoor workers in informal occupations such as motorbike drivers are at greatest risk and may already spend over half of productive working hours enduring high levels of heat stress, forcing them to choose between their income and their safety. Heat exposure in the leisure sector is also likely to impact workers in tourism, food, retail, and hospitality. These workers are predominantly indoors engaged in manual labor without air-conditioning, conditions which generate average workability losses of over 30 percent across the year.9 Losses also are concentrated in public administration, where production is most heavily reliant on labor as an input, with reduced labor productivity here having a disproportionate impact on the sector’s overall output.

Extreme heat is a major contributor to energy poverty, reducing access to active cooling. In May 2016, following the worst heat wave in sixty-five years, energy consumption reached a national record high.10 This disproportionately impacted Bangkok residents, who have an average monthly electricity bill (THB 1,133/USD 33) that is 3.1 times higher than households in northeast Thailand (THB 367/USD 11)11 and equivalent to more than 11 percent of household expenditure for laborers, a particularly heat-exposed group.12 With active cooling unavailable or unaffordable, health impacts can be severe. Heat stroke and food poisoning resulting from bacteria growing rapidly on unrefrigerated food in hot temperatures are both likely to increase.13

Note on “Projected number of hot and extremely hot days”: Days where the twenty-four hour average (i.e., daily) temperature exceeds the local 90th percentile of the baseline average daily temperature are defined as “hot days,” while days where the daily temperature exceeds the local 97.5th percentile are defined as “extreme hot days.” Because hot days are relative to typical local temperatures, the same daily temperature may be considered “hot” in one city but not another. The baseline is based on historical climate data, 1985-2005, while 2050 is based on the 2040-2060 climate from an ensemble of CMIP6 models under RCP 7.0. Source: Vivid Economics.

Note on “Productivity losses by sector”: The agricultural sector captures loss within the defined city limits and does not account for agricultural loss from the surrounding rural areas. Baseline losses are based on historical climate data from 1985-2005 and economic data from 2019. 2050 losses are based on the 2040-2060 climate projection from an ensemble of CMIP6 models under RCP 7.0 and economic models under SSP3. Losses assume no change in sectoral composition of economy. Source: Vivid Economics.

Note on “Active cooling coverage and heat related productivity losses by sector”: O*NET, 2021; and analysis by Vivid Economics.

Extreme heat interventions

Local authorities are taking steps to reduce losses from heat across the economy, but the current high level of losses illustrates the urgency of further action. Bangkok Metropolitan Administration plans for climate action present an opportunity for ambitious regulation and investment targeting extreme heat and its equally extreme impacts.

- Planning/policy: Existing legal protections include Thailand’s occupational heat standard, revised in 2016, which uses wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT)17 as an index to estimate heat stress. The law limits the amount of effort that is permitted in manual work beyond specified WBGT thresholds. A 2021 study found that the occupational heat standard protects four out of five workers in workplaces that comply with the standard.18

- Investment in the built environment and nature-based solutions: The Bangkok Master Plan on Climate Change 2013–2023 has numerous actions to address extreme heat such as improving insulation performance, introducing thermal barrier roof coatings, roof and wall greening, and controlling solar radiation heat by installing louvers or eaves in buildings.19 Other nature-based approaches have included increasing new green areas, such as public parks, planting new trees along roadside areas, and reforesting urban mangroves.20

Explore more city chapters

Return to the global summary

Endnotes

1 To estimate economic losses, this study goes beyond political boundaries to give a sense of how extreme heat and humidity impact Bangkok’s influence area. Core economic modelling considers the Bangkok Metropolitan Region. The regional approach is to ensure that analysis covers populations that are central to Bangkok’s growth and urban trajectory.

2 All analysis is based on RCP 7.0 and SSP3, using an ensemble mean of CMIP6 models; see accompanying methodology document for details.

3 See, for example, M. Wolff and D. Haase, “Mediating Sustainability and Liveability—Turning Points of Green Space Supply in European Cities,” Frontiers in Environmental Science 7 (2019): 61, doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2019.00061.

4 Analysis by Vivid Economics, based on summer average land surface temperature (LST), modeled climate data for 2050, and analysis of expected UHI and urban development from Kangning Huang et al., “Projecting Global Urban Land Expansion and Heat Island Intensification through 2050,” Environmental Research Letters 14, no. 11, 2019, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4b71.

5 The workability analysis is based on climate factors and not indoor working conditions determined by built environment characteristics or workplace layout (e.g., equipment that generates heat, body heat in close spaces, ventilation or greenhouse effects from windows, external shading). In practice, some of these factors can make indoor environments hotter than the modeled climate conditions suggest. All output is measured based on gross value added (GVA), or the value of goods and services produced in an area.

6 Numbers are approximate and rounded to the nearest 10. Exchange rates from International Monetary Fund (2022). 2021 annual average exchange rate – 34.09 THB/USD. Available at https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61545850.

7 Economic data in this report are from 2019 to avoid capturing the effect of COVID-19 on the economies of the cities analyzed; see methodology for further details.

8 Steve Saxon et al., “Reimagining Travel: Thailand Tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic,” McKinsey & Company, November 30, 2021, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/reimagining-travel-thailand-tourism-after-the-covid-19-pandemic.

9 “Thailand Gears Up to Protect its Tourism Sector from Climate Change,” Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), June 4, 2019, https://www.thai-german-cooperation.info/en_US/thailand-gears-up-to-protect-its-tourism-sector-from-climate-change/.

10 Weather News (2016): Extreme Heat Sears Southeast Asia With All-Time Records; Worst Heat Wave in Thailand in 65 Years. Available at: https://weather.com/news/weather/news/thailand-southeast-asia-extreme-record-heat.

11 National Statistical Office of Thailand (NSO), “Major Findings of the 2013 Household Energy Consumption, 2014, https://data.opendevelopmentmekong.net//dataset/major-findings-of-the-2014-household-energy-consumption.

12 Sigit Arifwidodo and Orana Chandrasiri, “Urban Heat Island and Household Energy Consumption in Bangkok, Thailand,” Energy Procedia 79 (November 2015): 189-194, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876610215021931; and NSO, “Major Findings.”

13 Associated Press, “Scorching Heat Wave in Thailand Is Longest in 65 Years,” Chicago Tribune (website), April 17, 2016, https://www.chicagotribune.com/nation-world/ct-thailand-hot-april-20160427-story.html.

14 Discover Walks Blog (2021). A Brief Guide to Bangkok’s Motorcycle Taxis. Available at: https://www.discoverwalks.com/blog/a-brief-guide-to-bangkoks-motorcycle-taxis/.

15 Arphorn et al. (2014). Working conditions and occupational accidents of informal workers in Bangkok, Thailand: A case study of taxi drivers, motorbike taxi drivers, hairdressers and tailors. J.Science of Labour Vol.90, No. 5. Available at: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/isljsl/90/5/90_183/_pdf/-char/ja.

16 Tawatsupa et al. (2013). Association between heat stress and occupational injury among Thai workers: findings of the Thai Cohort Study. Ind Health. 2013;51(1):34-46. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23411755/.

17 See accompanying methodology for further details.

18 Wantanee Phanprasit et al., “Climate Warming and Occupational Heat and Hot Environment Standards in Thailand,” Safety and Health at Work 12, no. 1 (March 2021): 119-126, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2093791120303383; 45 percent of workers were employed in workplaces that do not adhere to it due to legal ambiguities and compliance issues.

19 The Bangkok Master Plan on Climate Change 2013–2023: Executive Summary, Japan International Cooperation Agency in collaboration with Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, September 2015, https://www.jica.go.jp/project/thailand/030/materials/ku57pq00003snuz2-att/summary_en.pdf.

20 Bangkok Metropolitan Authority, “Bangkok Master Plan on Climate Change 2013–2023,” Leaflet, https://webportal.bangkok.go.th/upload/user/00000231/web_link/air/Kleaflet.pdf.